Before Israel: When Arab Jews, Christians and Muslims Coexisted

Before the establishment of the ethno-religious state, Jews, Christians, and Muslims shared Middle Eastern cultural hubs and lived experiences. All of that vanished with the arrival of Zionism.

Once upon a time, the Middle East was home to diverse communities of Arab Jews, Christians, and Muslims. Believe it or not, these communities lived side by side for millennia.

Throughout the culturally rich region, these groups shared languages, commerce, and traditions, weaving a social fabric largely defined by collaboration and interdependence.

Life Under Dhimmi Law

In the centuries before the arrival of modern Zionism in the region, Arab Jews, Christians, and Muslims were governed by the dhimmi system, overseen by the religious majority—Muslims.

This legal framework under Islamic rule governed the status and rights of non-Muslims, particularly Christians and Jews, who were referred to as dhimmi, or “protected people.”

In exchange for paying a tax called the jizya and agreeing to limitations on building new places of worship or bearing arms, dhimmi communities were granted freedom and autonomy in personal and communal matters, as well as protection from external threats.

Contrary to what many believe, Jizya wasn’t a head tax. Instead, it functioned more like protection money, paid by non-Muslims to Muslim rulers in exchange for safeguarding their communities.

To be clear, this system was far from perfect. By placing non-Muslims in a subordinate position to Muslims, its inherent institutional hierarchy made true equity impossible.

Admittedly, however, it also provided a degree of stability and relative peace, allowing religious minorities to maintain economic and cultural identity, in many regions of the Islamic world (restrictions were inconsistent across time and regions. In some Islamic societies, the restrictions were minimal or not enforced, while in others they were more severe).

Given the historic and cultural timeframe, it’s worth noting that the dhimmi system, for all its flaws, was comparatively less extreme than contemporaneous dictates in many “Dark-Age” European nations, in which forced conversions, expulsions, and executions were common practice.

Dhimmi law was far more permissive with regard to outgroups (Jewish and Christian communities) than the apartheid system that operates today under Israeli occupation.

Today, Muslims and Christians alike face systemic discrimination, enduring displacement and restrictions on movement, construction, and religious or cultural practices.

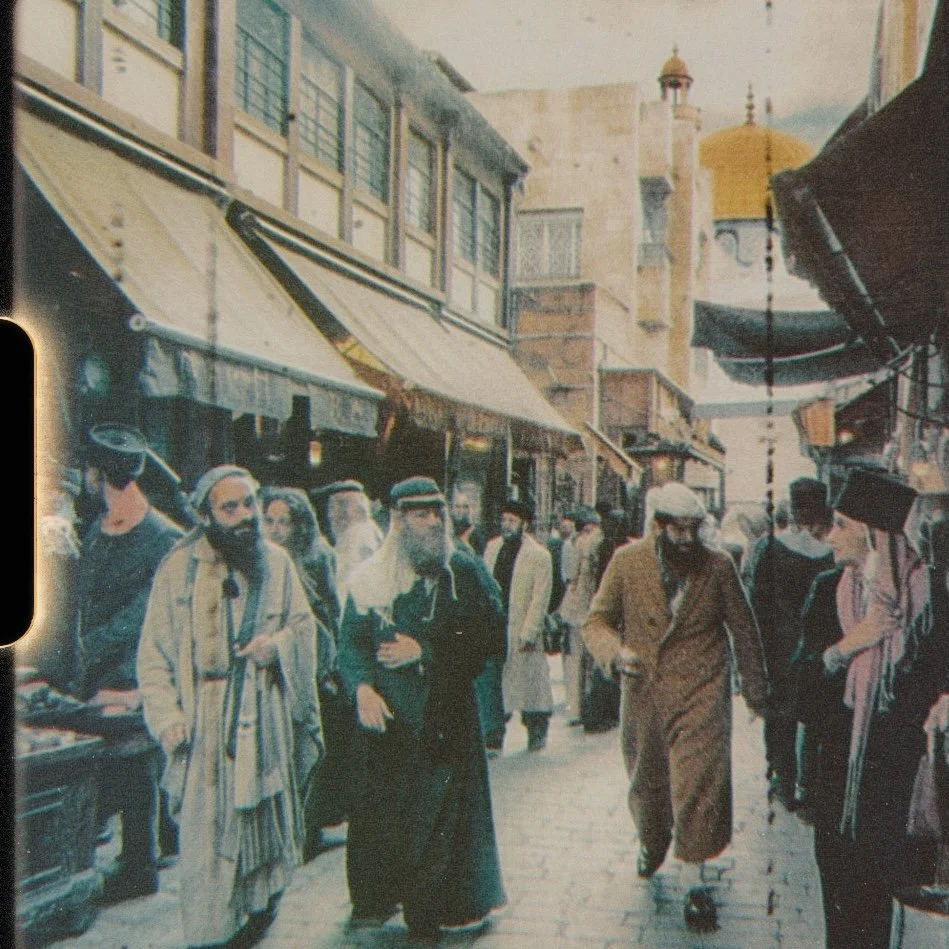

Depiction of bazar life Baghdad, Iraq in early19th century

Hubs of Cultural Significance

All things considered, and obvious exceptions notwithstanding, the Middle East had, to this point, fostered a comparatively tolerant coexistence among its diverse religious groups.

Arab Jews, Christians, and Muslims lived alongside one another in cities that ultimately became major cultural hubs, participating in shared cultural and economic activities.

A number of these areas represented key points along the Silk Road and other vital trade routes.

Under the Abbasid Caliphate, Baghdad became a renowned center of learning and commerce, hosting scholars, scientists and merchants from across the world in its famous House of Knowledge.

Meanwhile, given its strategic location along these routes, Damascus fostered exchanges of goods and ideas, becoming an international city of cultures.

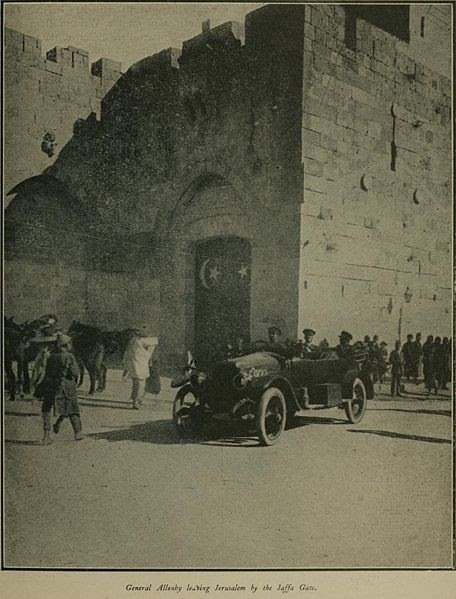

Jerusalem, revered by all three Abrahamic faiths, embodied the coexistence of synagogues, churches, and mosques within the same cityscape.

The Millet System and Changing Dynamics

In 1492, following the expulsion of Jews from Spain under the Alhambra Decree, Sultan Bayezid II welcomed the many Sephardim who sought refuge within the Ottoman Empire, recognizing the potential benefits they could bring to his realm. Bayezid reportedly criticized the Spanish monarchs for their decision, suggesting that their loss was the Ottoman Empire's gain.

Sephardic immigrants were integrated into the emerging millet system, which had evolved from and eventually replaced the dhimmi framework.

After conquering Constantinople, the Ottomans absorbed many Greek Orthodox, Armenian Christians, and Jewish communities. The millet system formalized the jurisdiction of these distinct religious groups, granting them autonomy in internal matters like tax collection, governance, and legal disputes.

Over time, the millet system adapted to the empire’s administrative needs, particularly as its population grew more diverse.

However, the Tanzimat reforms of the mid-19th century sought to centralize governance and promote equality among all subjects, gradually reducing the autonomy of religious communities and shifting toward the concept of “Ottoman citizenship.”

Of course, all of this was about to change, yet again with the arrival of European Zionists in the late-19th century. The millet model was disrupted due to colonial interventions and the expiration of the British Mandate —that would become Israel and fracturing the precarious balance that had defined the region for nearly 1200 years.

A Region on the Brink

The turn of the 20th century was a time of profound upheaval for the Middle East. The collapse of the Ottoman Empire following World War I had left a power vacuum in a region that had been under its rule for centuries.

With the foundation of the League of Nations, Western colonial ambitions became formalized, as European powers divided territories under the guise of international oversight.

Despite being presented as a blueprint for global peace and stability, the Covenant of the League of Nations was, in reality, an agreement by predominantly white European nations to decide among themselves which powers would rule over vast regions inhabited by non-European peoples.

This approach entirely disregarded the aspirations of the indigenous populations, reducing them to pawns in the colonial chessboard of empire-building.

Simultaneously, the Balfour Declaration of 1917, in which Britain unilaterally promised support for a Jewish homeland in Palestine, set the stage for further division.

These maneuvers culminated in the dispatch of the King-Crane Commission in 1919.

The commission was led by Henry Churchill King, a Protestant theologian, and Charles R. Crane, a self-imagined missionary, divinely commanded to spread Western Christian values, particularly throughout the Middle East and the broader former Ottoman territories.

On the order of Woodrow Wilson, by way of his Fourteen Points speech, the two oversaw the commission, officially titled the Inter-Allied Commission on Mandates in Turkey, which was tasked with determining the wishes of the local population regarding the governance of the former Ottoman territories and European mandates.

What the commission found was a population virtually unanimous in its desire of a pan-Arab state, not controlled by a foreign power—a vision for a society that reflected the region’s shared cultural and linguistic heritage (Arabic, in its local dialects, was the lingua franca, as Hebrew had not been widely spoken, at least outside of Europe, for at least 1,700 years).

King-Crane commission, Hotel Royal. Beirut, Lebanon, 1919

During the commission, Palestinian and Jerusalemite representatives articulated overwhelming opposition to Zionism and colonialism, emphasizing their desire for independence as part of a larger Arab nation.

Residents warned that the establishment of a Zionist state would disrupt a fragile harmony and lead to inevitable conflict.

Collectively, they rejected European mandates and the effort to establish a Euro-Jewish state in the region.

The commission’s findings underscored these warnings. It explicitly recommended limiting Zionist ambitions, cautioning that the imposition of a Jewish homeland against the will of the majority would result in instability and violence.

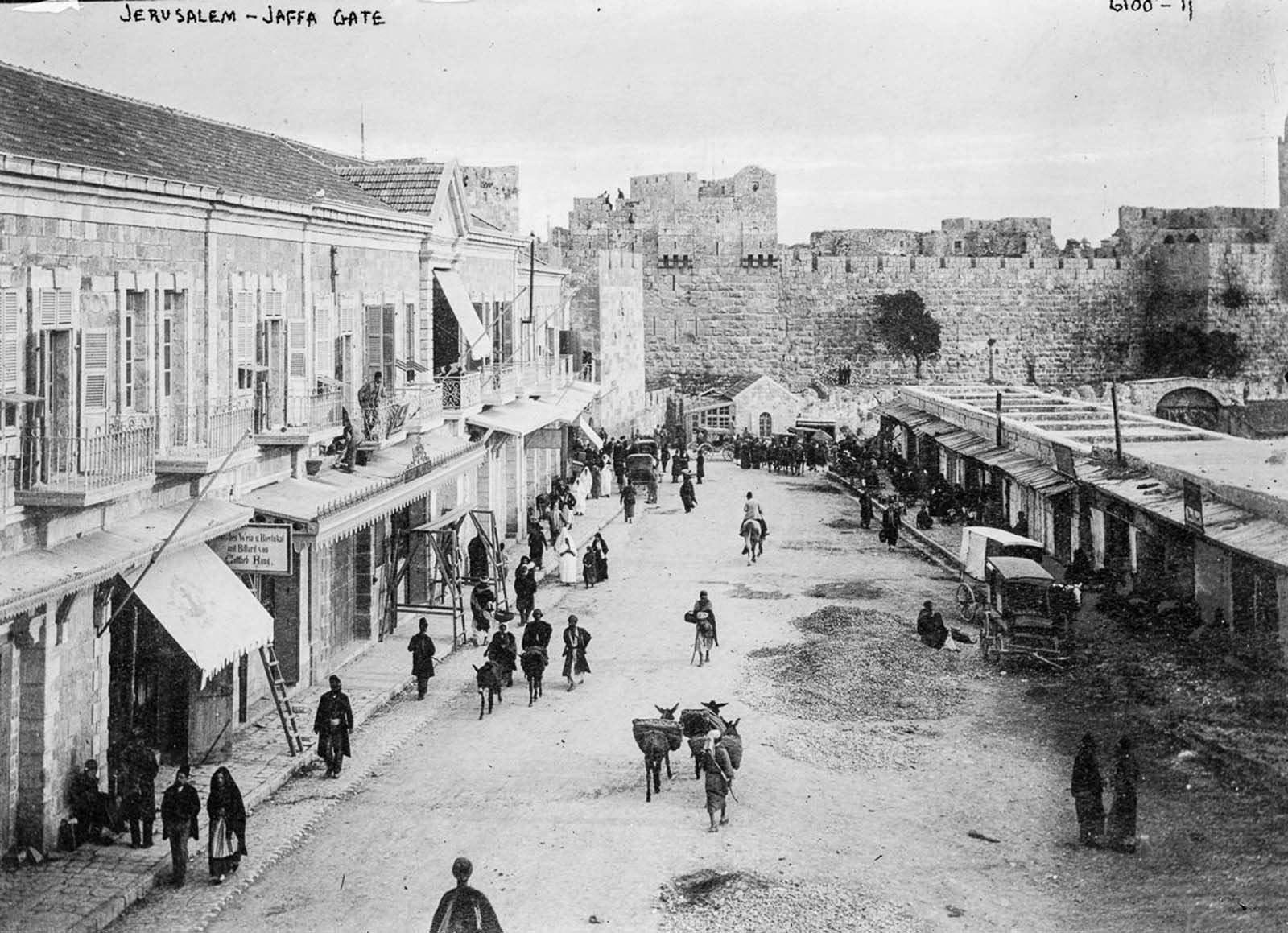

Palestine: A Land Very Much with a People

Although early Zionists promoted the slogan, “A Land Without a People for a People Without a Land,” evidence reveals that their leaders were fully aware of the reality from the very beginning.

From the early 1500s to the fall of the Ottoman Empire in 1917, Palestine, or Filastin, was the southernmost part of the empire's Syrian territories, and one of several administrative districts, known as sanjaks, within the Vilayet of Syria.

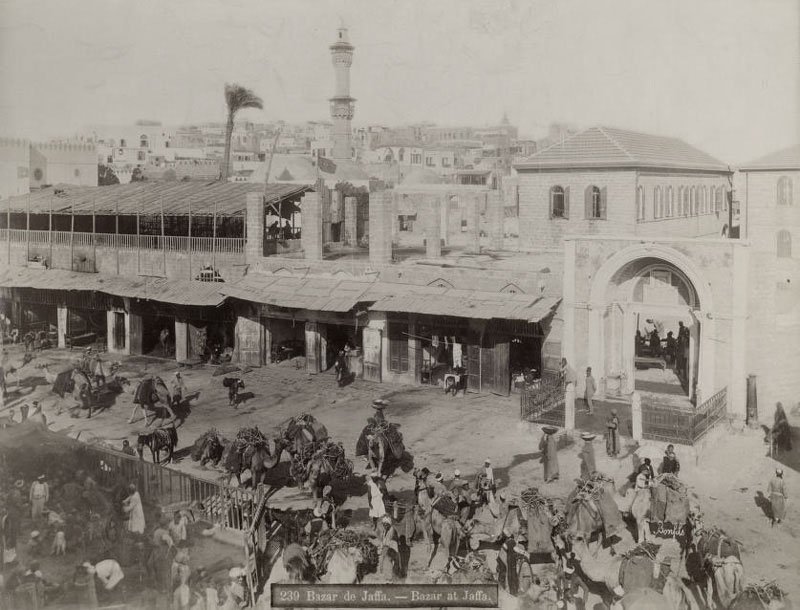

This period saw the region thriving as a hub of cultural and religious diversity, with cities like Jerusalem and Hebron, long known for its glassblowing history, maintaining their historical significance as centers of trade and spiritual life.

As Ottoman control waned, the desire for self-determination among the region's inhabitants grew, and Palestine became central to the vision of a unified Arab state.

Cities like Jaffa, Haifa, and Nablus emerged as bustling centers of lively political discourse and resistance against foreign forces, embodying the aspirations of a people determined to define their own future.

In the time between Balfour and the establishment of Israel, tensions grew to a boiling point. In 1920, during the twilight of British Mandate, Palestine was officially recognized as a political entity, with formal boundaries.

However, residents became increasingly concerned by the ambitions of the exponential influx of European Jewish immigrants—many of them undocumented and illegally residing in the region—after learning of plans to take control of the Western Wall.

Prior to the official opening of Haifa harbor in October 1933, boats from Germany and Eastern Europe were already using the port to disembark Jewish immigrants.

This influx of European Jews resulted in exponential expansion of Haifa’s Jewish population and intensified Arab concerns of Zionist migration, particularly as knowledge spread that an estimated 10,000 Jews had snuck into the region.

The situation was further exacerbated by reports from the Jewish press covering the Zionist Congress in Prague, where discussions on immigration caused alarm among Arab communities.

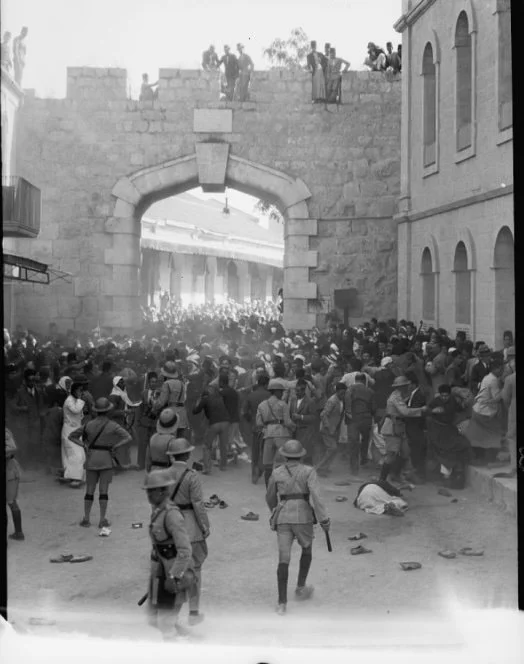

As Zionist immigration grew, so too did Palestinian resistance. In acts of desperation not unlike those to which the Dakota were driven by U.S. colonizers, the existential threat posed by Zionism prompted Palestinians to rise up in resistance against their own removal.

The 1920 Nebi Musa riots and the 1929 Hebron massacre were early signals of the rising tensions, as Palestinians opposed their displacement and the influx of European Jewish immigrants.

1933 riot arising from tensions between indigenous Palestinians and European Jewish immigrants.

By the 1936–1939 Arab Revolt, the region was militarized, with Palestinians fighting both British colonial forces and Zionist militias.

Soon, Zionist syndicates like the Haganah, Irgun, and later the Lehi (Stern Gang) began to organize militarily for offensive operations to establish their desired European Jewish state.

The Haganah

This group was already known for bombing a ship carrying Jewish refugees, killing 267. Under the training of Shlomo Hillel, an Israeli terrorist and eventual political figure, the Haganah carried out Plan Dalet, a strategy to depopulate Arab villages and secure land for the nascent State of Israel. Atrocities like the infamous Deir Yassin massacre, where over 100 Palestinian villagers were brutally raped, tortured and murdered, exemplified their methods.Irgun Zvai Le’umi

Irgun’s bombing of the King David Hotel in 1946, killed 91 people, including Arabs, Jews, and British officials, and injured 46 others. This attack destroyed evidence collected by British regarding previous Zionist terrorist attacks (the hotel housed the British administrative headquarters for Mandatory Palestine, including military, intelligence, and civilian offices).Lehi gang targeted British officials and Arab civilians, assassinating Count Folke Bernadotte, a United Nations mediator, in Jerusalem in 1948. Bernadotte had dared to propose compromises on the status of Jerusalem, which the Stern Gang opposed.

Plan Dalet was a systematic military strategy implemented by Zionist militias in 1948 to secure territory for the nascent State of Israel by forcibly depopulating Palestinian villages and towns.

It involved coordinated attacks, expulsions, and massacres, such as the infamous Deir Yassin massacre, where 245 villagers were violently murdered, to ensure control over key areas and prevent the return of displaced Palestinians.

Contemporaneous newsreel covering the bombing of the King David Hotel. (Associated Press)

Plan Dalet’s Other Victims

Dayr Muhaysin

A village rich with orchards, vineyards, and olive trees, located near the western entrance to the Jerusalem corridor.

Dayr Muhaysin was strategically important due to its proximity to the Jerusalem corridor and its role in the local agricultural economy. Its lush terrain made it a key target during Operation Nachshon.

The village was occupied by Haganah forces on April 3, 1948, as part of the operation to secure the route to Jerusalem. Dayr Muhaysin’s residents fled during the assault, and the village was subsequently depopulated and destroyed.

Khulda

A village known for animal husbandry and rainfed agriculture, situated near the western entrance to the Jerusalem corridor.

Khulda specialized in grain cultivation and small-scale vegetable farming, with its lands integral to the local economy. Its location along the Jerusalem corridor made it a target during the operation.

The village was captured by Haganah forces on April 3, 1948, without significant resistance. Khulda was systematically destroyed with bulldozers on April 20. Today, Kibbutz Mishmar David exists on its ruins.

Qaluniya

A small Arab village located just west of Jerusalem, along the road to the city.

Qaluniya was strategically important because of its proximity to the main road connecting Jerusalem to the coastal plains.

The village was attacked and captured by Haganah forces on April 11, 1948, during Nachshon. Its residents fled during the assault, and the village was subsequently depopulated and destroyed. Qaluniya's land was used for Israeli development, forever erasing its presence from the landscape.

Al-Qastal

A strategically located village near the Jerusalem—Tel Aviv Road.

Al-Qastal was crucial for controlling the supply route to Jerusalem. It was heavily fortified by Arab forces and became a focal point of the battle during Operation Nachshon.

The village was captured by Haganah forces on April 9, 1948, after intense fighting. Abd al-Qadir al-Husayni, who “led a desperate counter-attack to recover the village,” was killed during the battle.

Beit Surik

A small village situated near the Jerusalem Corridor.

The village of Beit Surik, nestled northwest of Jerusalem, was given the title of the "Guardian of Jerusalem" by Mamluks during the Fatimid Caliphate (909–1171)—a legacy it upheld until the devastating events of the Nakba.

On April 15, orders were issued to attack the village with the aim of "annihilation and destruction and arson." On the night of April 19, the village was surrounded, and after a brief mortar barrage, it was captured. Later, a special unit contaminated the village wells with a biological warfare agent consisting of typhus and diphtheria bacteria, aiming to hinder any attempts by villagers to return to their homes.

Beit Mahsir (Bayt Mahsir)

A large village located on the hills west of Jerusalem.

Beit Mahsir was a key position for Arab fighters attempting to block Jewish supply convoys.

The village was heavily bombarded and captured by Haganah forces, resulting in its depopulation and eventual destruction. Today, it is occupied under by the settlement Beyt Me'ir.

Bayt Naqquba

A small village situated west of Jerusalem, near key strategic locations such as Al-Qastal and Qaluniya.

Bayt Naqquba was strategically located in the Jerusalem corridor, making it a target for Zionist forces during Operation Nachshon. Its capture was likely part of the broader effort to secure supply routes to Jerusalem.

The village was captured in early April 1948. Following the assault, its residents were displaced, and in 1949, the Israeli settlement of Beyt Neqofa was established on the village's lands. A few original houses remain today, repurposed as dwellings or stables.

Saris

A village located near the main road to Jerusalem.

Like Qaluniya and Al-Qastal, Saris was strategically important for controlling the supply route.

When the village was attacked on April 16, 1948, seven villagers, including women, were killed. The remaining residents were expelled. The entirety of the village, approximately 25–35 buildings, was destroyed. Today, the settlement of Shoresh exists upon its ruins.

Dayr Ayyub

A village near Bab al-Wad (Sha’ar HaGai), a key choke point on the road to Jerusalem.

The village of Dayr Ayyub was a stronghold for Arab forces defending the corridor.

Zionist forces attacked and captured Dayr Ayyub, leading to its depopulation. Today, underground shelter has been built on the site, and military trenches can be seen north and east of the fortress.

Abu Shusha

A village near Latrun, which was strategically vital for controlling access to Jerusalem.

Abu Shusha was targeted as part of the effort to clear the surrounding areas.

The village was attacked, and its residents were forced to flee. Today, the Ameilim settlement stands on its ruins.

Suba (Soba)

A hilltop village near Qaluniya and Al-Qastal.

Suba served as a vantage point for Arab forces defending the area.

The village was attacked several times by the Haganah, and finally conquered by the Palmach during the night of July 12–13 as part of Operation Danny. Most of the inhabitants had fled during the fighting, and those who remained were expelled.

In October 1948, the "Ameilim" group of Palmach veterans established a kibbutz called Misgav Palmach on village lands 1 km to the south. Later it was renamed Tzova.

Of course, these are but a small fraction of the number of villages and people who were erased from the land during the Nakba.

Recommended Viewing: Born in Deir Yassin, a documentary detailing the horrific massacre at titular village.

The Spread of Zionism in Iraq

As these Zionist militias waged terror campaigns to secure their colonialist ambitions in Palestine, a parallel network of underground Zionist movements operated in Arab nations like Iraq.

The Zionist underground in Iraq, described as a "multi-tentacled octopus," coordinated efforts that mirrored those in Palestine.

Ha'modieyin, the intelligence branch, gathered critical information on military operations and infrastructure, forwarding this data to Israeli intelligence services.

Ha'shura, the militant defense branch, trained Jewish youth in the use of weapons and explosives, preparing them to defend against perceived threats while advancing Zionist goals.

Ha'halutz, the cultural and educational arm, indoctrinated young Jews in Zionist ideology, assimilating them into the Euro-Zionist view of “Israeliness” readying them for immigration to while excommunicating them from their Arab heritage. Ha'halutz was the largest branch of the movement.

Ha'aliyah, was the operation facilitating Jewish immigration to Israel. Initially, its focus was solely on clandestine, illegal migration efforts, operating continuously as the sole avenue of relocation. After passage of a law allowing Iraqi Jews to renounce their citizenship, the operation expanded, splitting into two distinct branches: one working openly within legal frameworks and the other remaining undercover to handle covert activities.

These branches operated with a singular focus: to advance the Zionist agenda by any means necessary, whether through cultural reprogramming, militant action, or covert espionage.

Wanted poster for Lehi (Stern Gang) members Jacob Lebstin, Yitzhak Yazernitsky and Nathan Friedmaneilin for the assassination of Folke Bernadotte

Ha’shura bombings of Jews in Iraq and Subsequent Migration

The role of Ha’shura, the militant arm of the Zionist underground in Iraq, in the 1950–1951 Baghdad bombings remains one of the most shocking chapters in modern Middle Eastern history.

Allegations supported by forensic evidence, testimony, and trials suggest that these bombings were part of a Zionist strategy to expedite the mass migration of Iraqi Jews to Israel.

Laboratory analyses revealed a direct connection between the materials used in the bombings and Zionist propaganda tools.

During the proceedings, Anti-American leaflets found at the American Cultural Center bombing were confirmed to have been typed on the same typewriter and duplicated using the same stencil machine employed by the Zionist movement in Baghdad.

Additionally, the explosives used in another attack were identical to those found in the possession of Yosef Basri, a lawyer and member of Ha’shura.

Basri, along with Shalom Salih, a shoemaker, and a third conspirator, Yosef Habaza, confessed to carrying out the attacks during their trial in December 1951. Habaza recanted, stating that his confession was coerced through torture.

Basri and Salih were executed in January 1952, while Habaza’s fate remains less documented, with some accounts alleging he spent the 50s in prison before travelling to Israel.

These terrorist actions coincided with escalating fears within the Jewish community, which contributed to a mass exodus of nearly all of Iraq’s 125,000 Jews to Israel under Operation Ezra and Nehemiah.

This exodus was further compounded by the Iraqi government’s freezing of Arab-Jewish property and assets, an action likely taken in response to Irael freezing the entirety of financial wealth among Palestinians they were simultaneously ethnically cleansing from the region.

Such financial woes continued upon arrival in Israel, where Iraqi Dinars were exchanged at a punitive rate, with the Israeli government seizing 50% of their value.

End of a Pan-Arab Aspirations

Despite a clear Arab preference for a free, united Arab state, asserted by King-Crane decades earlier, Western powers moved forward with their plans, ultimately ensuring that imperialist interests trumped local autonomy.

The establishment of Israel in 1948, facilitated by the Balfour Declaration and a complete disregard of the King-Crane Commission’s findings, marked the end of any semblance of hope for a pan-Arab state.

The delicate balance that had, up to that point, allowed for coexistence among Arab Jews, Christians, and Muslims was soon to be replaced by fragmentation, systemic exclusion, displacement, and no small amount of barbaric violence.

Arab Jews were alienated from their cultural and religious heritage, in favor of inculcation with a Westernized framework that erased their ties to the broader Arab world.

Arab Christians, who had played a vital role in the region’s political and cultural life, were increasingly marginalized and displaced alongside their Muslim neighbors.

Zionism, with its supremacist and anti-Arab premises, destroyed not only the coexistence of the past but also any possibility of a unified and pluralistic future.

Even worse, the movement purposely conflated Zionism with Judaism to an extent that the modern layperson is apparently unable to distinguish between the two.

A Legacy of Division

The story of pre-Zionism Palestine is one of missed opportunities and deliberate betrayal. The people of the Middle East, despite their religious differences, sought a shared future under a pan-Arab state, rooted in mutual respect and cultural plurality.

The Zionist project, explicitly discouraged in the commission’s report, was imposed through foreign interference and upheld by violence, extinguishing that possibility.

To move forward, it is essential to confront the colonial and nationalistic foundations of Israel and its destructive impact on the region.

Decolonization—both of the land and of the historic narrative—offers a path to reclaiming the coexistence that once defined the Middle East. This involves acknowledging the injustices of the past; from the displacement of Palestinians to the marginalization of Arab Jews and Christians striving for a future built on justice and equality.

The King-Crane Commission’s warnings about the consequences of overriding the will of the majority have been tragically validated by decades of ethnic cleansing, genocide and apartheid.

The time has come to finally right these historic wrongs, dismantle systems of power and rebuild the region on principles of pluralism and mutual respect, honoring the coexistence that was once possible.