The Hanging of the Dakota 38: A Story of America the Brutal

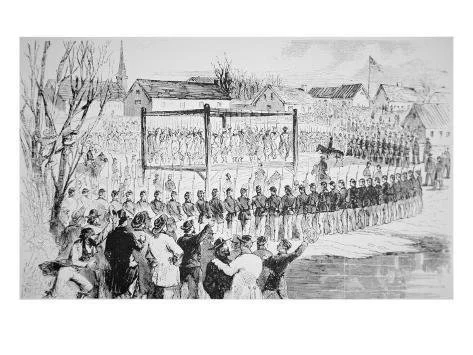

The hanging of the Dakota 38, the day after Christmas, 1862

The Lincoln-sanctioned “Christmas Hanging” exposes the brutal legacy of U.S. colonialism, where systemic oppression and dehumanization of Indigenous people extended beyond life into death.

On the day after Christmas, in the bitter cold winter of 1862, the largest mass execution in United States history took place in the small town of Mankato, Minnesota.

Thirty-eight Dakota (Dakȟóta) men stood on the gallows, their voices carrying in defiant song as land-stealing settlers gathered below to watch them die. This event was a travesty of justice, and demonstrative of America’s ruthless westward expansion.

These men were not criminals by any metric that considered survival a human right—they were Dakota people defending their land, their communities, and their lives from an encroaching empire.

For the Dakota, the scars from this execution have lingered through generations, rooted in memories of betrayal, hunger, displacement, and the relentless assertion of American power.

Additional perspective of the hanging of the Dakota 38

A Land Under Siege: The Dakota and the U.S. Expansion

The Dakota people, referred to by white settlers as the Sioux (a disparaging name used by the rival Ojibwa people meaning “little snakes”) were stewards of their ancestral lands for centuries, living sustainably across what is now known as Minnesota.

For the Dakota, every river, hill, and prairie held deep spiritual significance—a testament to a profound connection with the land that nourished them. However, with the implementation of the U.S. government’s expansionist agenda in the mid-19th century, this sacred connection faced unprecedented threats.

In a series of coerced treaties, the U.S. government extracted vast stretches of Dakota land.

The Treaty of Traverse des Sioux (1851) and the Treaty of Mendota (1851) were particularly devastating, as they transferred nearly all Dakota land to the government in exchange for small parcels of land and promises of compensation.

These treaties—representing only a small fraction of the more than 500 such agreements the U.S. would violate—promised compensation to the Dakota in exchange for 21 million acres of their ancestral lands.

However, much of the money intended for the Dakota was diverted to pay off debts claimed by dubious traders.

These debts, which the Dakota were reportedly further coerced into acknowledging, significantly reduced the funds and resources they actually received.

At Traverse des Sioux, for example, an estimated $275,000 of the treaty’s payments were allocated directly to traders under what were known as "Traders’ Papers."

Further treaties, such as the Yankton Treaty in 1858, continued this pattern of land loss, relegating the Dakota to ever-smaller reservations.

Broken Promises, Exploitation and Growing Desperation

For these communities, who had been self-sustaining before American interference, dependence on U.S. entities only deepened their vulnerability.

While the treaties promised annuities and supplies in exchange for land, these things seldom materialized. Payments were delayed or withheld, resources became scarce, and settlers poured into Dakota lands, stripping the forests, hunting the animals, and farming the soil.

Adding to the tensions was the behavior of the traders themselves. As Isaac V. D. Heard noted in History of the Sioux War and Massacres of 1862-1863, “The enormous prices charged by the traders for goods, by their debauchery of their women, and the sale of liquors, which were attended by drunken brawls that often resulted fatally to the participants,” further inflamed frustrations among the Dakota.

This practice not only deepened economic disparities but also contributed to a cultural and social breakdown, as liquor sales and abusive practices undermined the Dakota’s ability to maintain stability and order in their communities.

This practice of withheld payments, unethical behavior, and degrading treatment stoked resentment between the Dakota and the settlers.

The Dakota were not only deprived of financial means to sustain their communities but were subjected to systemic exploitation that stripped them of their rights to self-sufficiency and agency, pushing them ever closer to the brink.

By the summer of 1862, tensions were at a breaking point. The infamous words of trader Andrew Myrick— “If they are hungry, let them eat grass”—echoed throughout Dakota camps, symbolizing the disdain settlers held for a people they viewed as obstacles to manifesting their destiny: to homestead the land for their own race (a concept that the Germans would later refer to as Lebensraum).

This contemptuous dismissal further emboldened Dakota leaders, who eventually faced the agonizing choice of waiting for annuities that might never arrive or fighting to reclaim their stolen resources.

The Acton Incident and the Outbreak of War

The Acton Incident is often cited as the moment when the U.S.-Dakota War began. On Sunday, August 17, 1862, four young Dakota men of the Wahpeton band came upon some chicken eggs in a nest at the farm of a white settler, and there was talk of stealing the eggs.

When one refused, his companion dared him to prove that he wasn’t afraid. The men proceeded to engage a white man nearby, Robinson Jones.

Following him to a white homestead where some white settlers were gathered, they suggested a shooting match between them and the white men present.

However, tensions quickly escalated, guns were drawn and the Dakota braves took down Jones, his wife, and three other settlers.

Realizing the implications the actions of these few would have on the whole of their people, the Dakota convened a council in which the group overwhelmingly argued in support of uprising.

They even disagreed with their chief, Ta-ó-ya-te-dú-ta, “Little Crow,” who, after debating deep into the night, finally said:

“Braves, you are little children — you are fools. You will die like the rabbits when the hungry wolves hunt them in the Hard Moon.

Ta-ó-ya-te-dú-ta is not a coward; he will die with you.”

They continued launching attacks on settler outposts, reclaiming food and resources while trying to force the removal of those who had taken over their land.

In an act of poetic justice, Andew Myrick was killed on the first day of the war and was found with grass stuffed in his mouth.

Major battles soon followed, including significant engagements at Fort Ridgely and New Ulm. These battles saw fierce resistance from the Dakota, who knew that victory meant the difference between life and annihilation.

Yet, the U.S. military response, led by Colonel Henry Hastings Sibley, was swift and merciless. The Battle of Wood Lake on September 23, 1862, ultimately sealed the Dakota’s defeat, forcing their leaders to surrender at Camp Release days later.

The Trials: A Mockery of Justice

Following the Dakota’s surrender, the U.S. government wasted no time in establishing a military commission to “try” the captured Dakota men.

These trials were, by any standard, a mockery of justice. Many trials lasted mere minutes, often conducted without translation or legal representation for the Dakota, most of whom did not speak English.

Some men were convicted based on hearsay or mistaken identity, condemned without a shred of concrete evidence.

In total, 392 men were tried, 303 sentenced to death, and 16 given prison terms. The remaining prisoners, nearly 1600 in number, were taken to Fort Snelling, where they were detained under harsh, inhumane conditions.

Lincoln’s Calculated “Mercy”

As the outcry from Minnesota settlers grew louder, President Abraham Lincoln intervened. With an eye on his political standing against the backdrop of a raging Civil War, Lincoln reviewed trial records to identify those he deemed most responsible.

To say Lincoln's handling of the defeated Dakota differed from his treatment of Confederate rebels would be an understatement. Despite the Confederacy causing the deaths of more than 400,000 American soldiers, not a single Confederate general or officer was sentenced to death by Lincoln.

Still, ever the politician, he realized the optics of sentencing over 300 people to death. He eventually reduced the number of condemned to 39, approving the death sentences for men he believed were directly involved in “massacres” of civilians (one of the condemned was pardoned, bringing the number 38.)

Much like his war-minded motives behind the emancipation of (some) enslaved African Americans, Lincoln's intervention in the Dakota trials was a calculated decision, carefully crafted to balance public opinion while avoiding the appearance of excessive leniency. Nevertheless, history has painted this white supremacist executioner as some benevolent “Father Abraham”

“Lincoln was an executioner”

A Cold December Morning in Mankato

On December 26, 1862, the town of Mankato, Minnesota, became the somber stage for the largest mass execution in United States history.

In the biting cold of that winter morning, a massive scaffold loomed in the town square, its grim purpose clear to the approximately 4,000 white settlers who gleefully gathered to witness the hanging of 38 Dakota men, as 1,400 U.S. troops in full battle dress looked on.

The condemned, bound and prepared for execution, stood together, brave even in the face of death. Their voices rose in unison, singing songs of their people—songs of defiance, of sorrow, and of identity.

The Dakota braves refused to cower before their captors or the jeering crowd, whose calls for vengeance reverberated across the square.

To the settlers, this was justice served—a retribution for white lives lost during the U.S.-Dakota War.

However, to the Dakota, it was an assertion of the unrelenting dominance of an empire that had stripped them of their land, their autonomy, and now, their lives.

The execution was meticulously orchestrated. A single lever would send all 38 men plummeting to their deaths simultaneously, a macabre efficiency designed to ensure a public spectacle of control and power. Eyewitness accounts describe the final moments: the Dakota men, heads held high, chanting their songs as the trapdoors opened beneath them.

One man’s rope snapped under the strain, and he was hauled back up and hanged again, a cruel display of disregard for human dignity.

For the Dakota people, the scaffold, this chilling platform of death, was a chilling symbol of their subjugation. It represented the culmination of years of broken promises, exploitation, and dehumanization.

The spectacle of public execution was not just a punishment for the men on the scaffold; it was a message to the entire Dakota Nation and other Indigenous peoples: resistance would be met with absolute and merciless force.

The trauma of that December morning was etched into the collective memory of the Dakota, carried forward in stories and songs, a stark reminder of the cost of defiance against the empire.

Desecration in Death: The Fate of the Dakota 38’s Bodies

Even in death, the Dakota men found no peace. After the execution, their bodies were hastily buried in a shallow mass grave by the Minnesota River, treated with the same disregard and indifference that had marked the trials and the execution itself. However, they would not remain there long.

Within days, settlers and medical professionals exhumed the bodies, stripping them of basic human dignity even in death. The remains of the Dakota men were not handled with reverence but instead became commodities in a grotesque cycle of exploitation.

One of the most infamous examples of this desecration involved Dr. William Worrall Mayo, who would later establish the Mayo Clinic, a globally renowned medical institution. Mayo acquired the body of one Dakota man from the mass grave, using it as a subject for anatomical study, dissection and medical experimentation.

While Mayo’s work would later earn him acclaim, this chapter of his history reveals the white supremacy with which the scientific and medical communities were complicit in systemically dehumanizing Indigenous people.

The body of a man who had been unjustly executed for defending his people’s right to survival became an instrument for study, his humanity erased, and his dignity deprived even in death.

Exile, Erasure, and the Long Shadow of Mankato

After the execution, it was decided to transfer the convicted men to Camp McClellan in Davenport, Iowa.

By April 1863, those who had been acquitted, along with fifteen to twenty women who had served at the Mankato prison, were reunited with the sixteen hundred Dakota still detained at Fort Snelling in what has been referred to as one of the first concentration camps.

While the convicted prisoners were transported to the new prison camp in Iowa, the remaining members of the Dakota community were forcibly relocated yet again.

On March 3, 1863, Congress passed "An Act for the Removal of the Sisseton, Wahpaton, Medawakanton, and Wahpakoota Bands of Sioux or Dakota Indians, and for the disposition of their Lands in Minnesota and Dakota" (12 Stat. 819).

On the 4th of July, that same year, Lincoln signed the Homestead Act further enabling the settlement of western territories, granting 160 acres of public land to settlers for a minimal fee.

This act authorized President Lincoln to designate new lands outside the boundaries of any state for the relocation of these Dakota bands, effectively annulling previous treaties and stripping them of their rights to their ancestral lands in Minnesota.

The legislation also provided for the sale of their former reservations to settlers, further facilitating the displacement.

Of course, in the end, most small farmers were unable to take advantage of the act due to fraud, land speculation and other misuse of its ambiguities , chiefly by the white ruling class.

As for the Dakota who remained—mostly women, children, and elderly— they were forced onto the barren Crow Creek Reservation in 1863.

The relocation, a distance of roughly 600 miles, was fraught with hardship, and things weren’t any better upon arrival. The Crow Creek Reservation was characterized by arid conditions, lack of resources, and an environment unsuitable for agriculture, leading to significant suffering among the displaced Dakota.

These hardships were particularly severe for the women, who comprised a majority of the displaced population.

At Crow Creek, some of the mothers had resorted to gathering undigested grains from passing horses’ feces to sustain their starving children. The scarcity of resources and the need to provide for their families compelled other women to resort to prostitution as a means of survival.

At both Crow Creek and Davenport, the Dakota were regarded as curiosities, with residents treating them as spectacles to be observed, akin to animals in a zoo.

Even those who had endured hell were not immune to the arrival of Indian schools

Forced Assimilation at Crow Creek

Eventually, Crow Creek would become home to Immaculate Conception Mission, an Indian Boarding School. From 1887 to 1975, more than 1,000 children were taken, many by force, never to be seen by their families again.

While many students came from the Crow Creek and Lower Brule Sioux tribes, children were taken from tribes across South Dakota and even as far as Wisconsin, Montana, Idaho, Oregon, North Dakota, Nebraska and Iowa.

This was part of a larger initiative to assimilate Indigenous children into European-American culture. As part of this, the Bureau of Indian Affairs allowed Christian missionaries to open new boarding schools across the United States, and in 1874 a group of Catholics in DC established the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions, a Roman Catholic charity institution.

A Legacy of Genocide and a Demand for Justice

To this day, the hanging in Mankato stands as one of the darkest, if largely unknown, moments in American history. It forever stands as a vivid example of the lengths to which the U.S. government will go in suppressing Indigenous resistance and enforcing its supremacist agenda.

To honor the legacy of the Dakota 38, we all must confront these injustices, not as distant events but as living histories that continue to shape the lives of Indigenous communities.

We must persevere by pushing toward a future where true liberation is more than just another American empty promise. We must come to the mutual realization that such a promise will never come from those who withhold that liberation from us.

In Mankato, Minnesota, the memory of the Dakota 38 endures. Their voices—silenced but never forgotten—remind us of the cost of empire and the enduring power of resistance.