Indian Schools and Cultural Genocide: An American Legacy

The lasting legacy of Indian boarding schools continues to fuel cultural erasure, but decolonization offers a path to reclaim Indigenous identity and sovereignty.

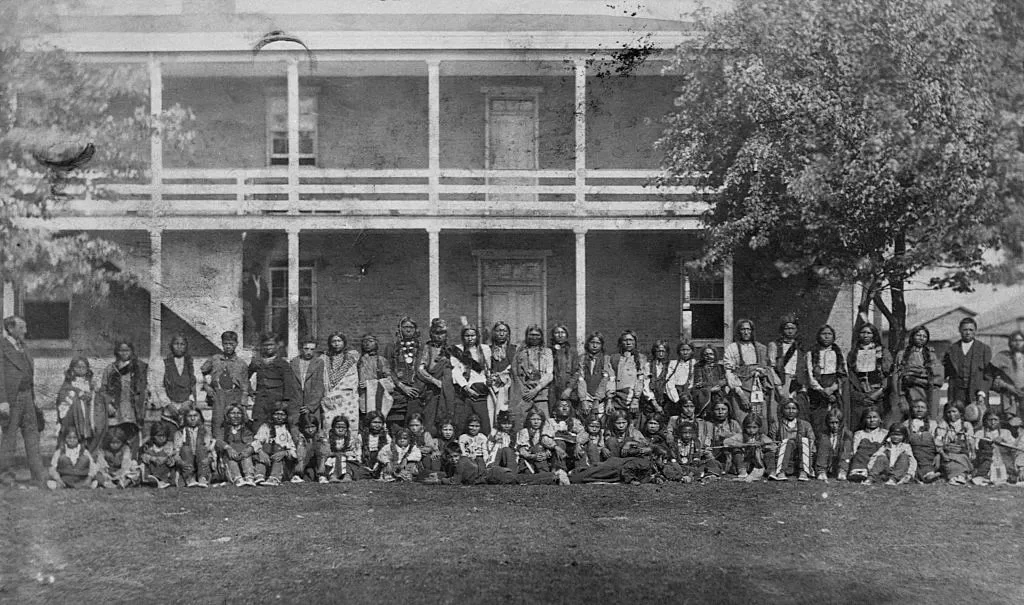

The history of Indian schools is perhaps one of the most devastating examples of colonialism in North America.

These institutions were founded with a clear goal: to forcibly assimilate Indigenous children into the dominant Euro-American society, erasing their languages, traditions and identities.

Although the schools themselves have since shuttered, the trauma and intergenerational harm they caused remain present in Indigenous communities today.

The assimilation era, which began in 1819 with the Civilization Fund Act, financed schools aimed at “civilizing” native youth.

Notably, the proliferation of these schools spread throughout so-called “free” states just as quickly as the “slave” states, suggesting that despite the rift arising from the treatment of enslaved Africans, the burgeoning nation was able to unite over a shared disdain for the Indigenous, and the coveting of their land.

This policy, which led to the establishment of the first on-reservation school in 1860, reached a peak with the founding of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania in 1879.

Carlisle, the first off-reservation boarding school, set the standard for hundreds of similar institutions, guided by Captain Richard Henry Pratt’s credo:

“Kill the Indian, save the man.”

Pratt’s philosophy laid the foundation for a century of systematic cultural genocide.

By 1926, nearly 83% of Indian school-age children were attending these schools.

By the 1970s, 357 federally and church-operated schools across 30 states housed over 60,000 Indigenous children, imposing Euro-American values and Christianity (the anglicized, appropriated version, anyways) through strict, abusive disciplinary measures.

The intent was to forcibly assimilate them into white American culture by erasing their identities.

The Indians must conform to the white man’s ways, peaceably if they will, forcibly if they must. They must… conform their mode of living substantially to our civilization.

This civilization may not be the best possible, but it is the best the Indians can get. They cannot escape it, and must either conform to it or be crushed by it…

The tribal relations should be broken up, socialism destroyed, and the family and the autonomy of the individual substituted.

- Thomas Jefferson Morgan, Commissioner of Indian Affairs, 1889

The Atrocities Committed in Indian Boarding Schools

The experiences of children in Indian boarding schools were marked by abuse, neglect and profound loss.

Children were forcibly removed from their families, sometimes torn from their parents’ arms as they tried to resist.

Once in the schools, they were forbidden from speaking in their native languages, practicing their cultural traditions, or even referring to themselves by their given names.

The use of corporal punishment was rampant, and the children who resisted or who could not adapt to the schools’ rigid routines faced brutal physical and psychological punishment.

In addition to the daily abuse and neglect, recent discoveries have revealed an even more horrifying reality.

Mass graves of Indigenous children have been found on the properties of former Indian boarding schools throughout North America.

These graves, many unmarked, contain the remains of children who died from disease, malnutrition, neglect, and abuse while attending these institutions.

Their deaths were often unreported, and their families left in the dark about what happened to them.

The erasure of life and the destruction of families that began in these institutions is a trauma that continues to ripple through Native communities to this day.

Intergenerational Impact: Cycle of Self-Loathing and Internalized Oppression

The trauma inflicted by Indian boarding schools did not end when survivors returned to their communities.

This trauma has created a profound internalized oppression and cultural disconnection for subsequent generations of Indigenous people.

Survivors had to navigate fractured identities, caught between the white-dominated society that sought to erase them and their ancestral cultures, from which they were forcibly excommunicated.

Many Indigenous people, having been raised in institutions designed to instill self-loathing, grew up falsely believing that their cultures were inferior or irrelevant.

This severance from a vital generational connection has led to a profound loss of cultural identity. The impact of this damage still endures among descendants, generations later.

In the absence of their once-sacred mores and traditions, these parents—shaped by their boarding school experiences—began unwittingly passing down the white supremacist beliefs forced upon them.

This has created untold subsequent generations of self-loathing descendants, many of whom remain oblivious to, and thus disconnected from, their rich heritage deeply rooted in this land.

Sadly, many such descendants have adopted the very culture that has marginalized them for centuries, siding with the oppressor, just as the system of the boarding schools had designed.

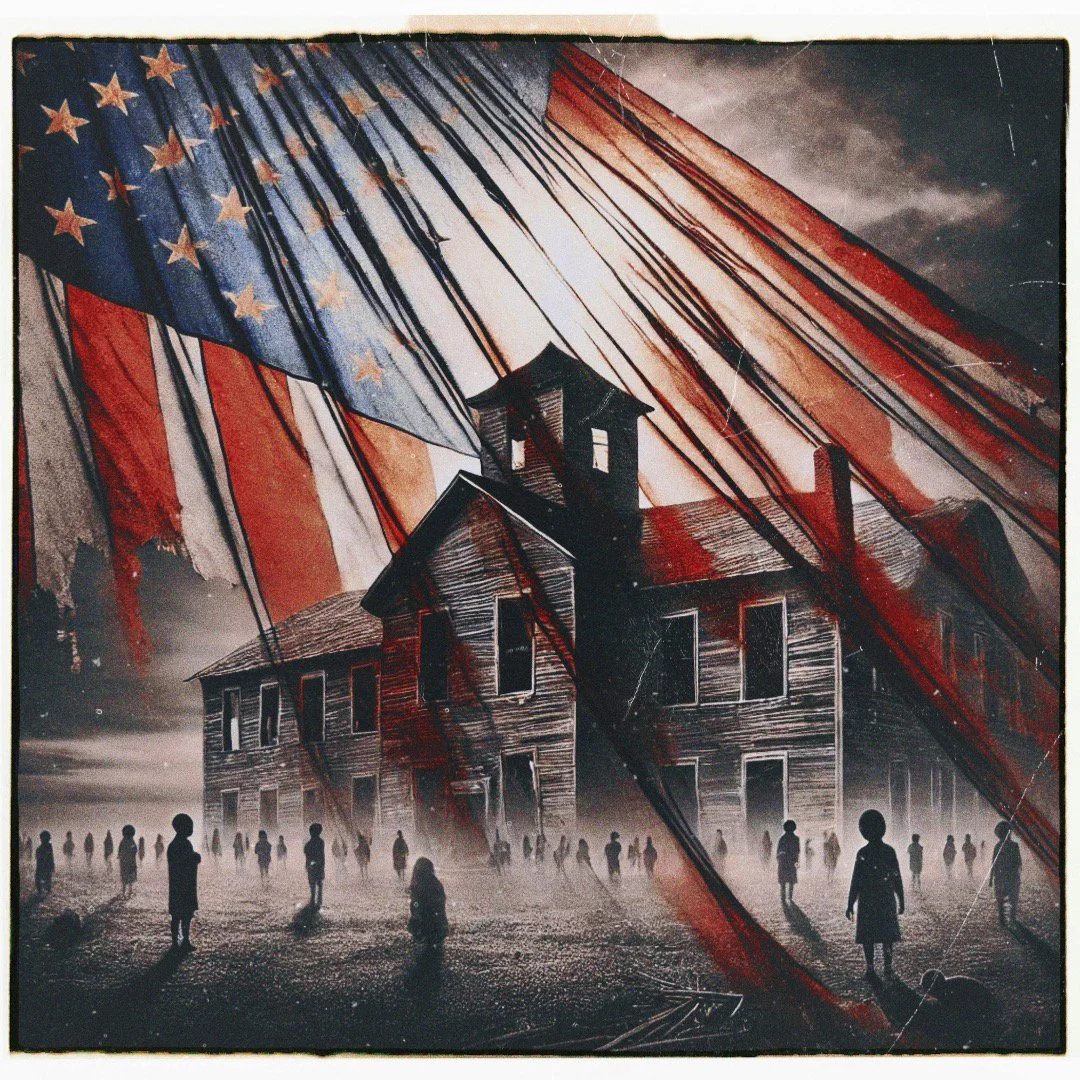

The Veil of the American Flag

The American flag, originally a symbol of brutish conquest and bloody colonization, now acts as a veil that obscures histories and cultures that once flourished on this land.

It demands allegiance from the descendants of those once massacred beneath its banner, while simultaneously denying them full acceptance into the society it represents.

For some, this forced allegiance is perceived as a matter of survival.

A number have even joined the American military—the occupying army, as it were—willing to fight and die for a country that has never truly valued them.

Of course, upon returning home, these soldiers often return to the same indifference, inequality and outright hostility that was there when they left.

Decolonization: Reclaiming Indigenous Sovereignty and Identity

Breaking the cycle of cultural erasure requires a process of decolonization. Decolonization is not just about reclaiming land—it’s also about reclaiming Indigenous identity and sovereignty.

The #LANDBACK movement is a critical part of this process, advocating for the return of stolen lands to their rightful stewards.

However, physical decolonization is only one part of the equation. Just as important is the decolonization of the mind—an effort to deprogram from the generations of cultural repression and learn to love one's true self, heritage and culture.

The decolonization of the mind involves undoing the internalized beliefs that have been ingrained through centuries of colonialism.

By rediscovering their roots and reasserting their cultural identities, Indigenous people can finally begin to heal from the generational trauma inflicted by Indian boarding schools and all manner of colonial practices.

Decolonization, both physical and mental, is the only way to breaking the cycle of self-loathing and internalized oppression that has plagued native people for far too long.

Reclaiming Indigenous Identity: A Fight Against White Supremacy

The fight to reclaim Indigenous identity is a fight against the forces of white supremacy and colonialism that have sought, for centuries, to erase it. Indeed, many of the descendants of those who scalped, defiled and subjugated the first peoples of this land continue their efforts today.

Indigenous communities must reclaim their cultures and histories to ensure that future generations are not subjected to the same oppressive forces that sought to erase their ancestors.

Only by fully understanding and actively resisting this cycle of indoctrination and cultural erasure can future generations truly recover their heritage and learn to celebrate it once again.