The Bracero Program, Operation Wetback, and the Colonial Cycle of Exploitation

The Bracero Program's labor exploitation and Operation Wetback's mass deportations reflect an American colonial mindset of using and discarding migrant communities, highlighting the inherent racism in US policy.

The mid-20th century marks a critical chapter in U.S.-Mexico relations.

More importantly, it marks a deep historical injustice: the exploitation of Mexican laborers on the very land that their ancestors once called home.

The period, now referred to as the “Braceros” era, was a time of labor exploitation—a reflection of the systematic denial of indigenous people's rights to their land and agricultural heritage.

These workers, Braceros, were descendants of the first people to pioneer agriculture in the region.

In a cruel twist of fate, they were exploited to cultivate the very same land that had been stolen from them by white settlers just a few generations before.

This displacement, enforced by legal regimes, racial hierarchies, and labor systems was designed to do two things: marginalize and extract.

To be clear, the Bracero Program did not create this imbalance, but it did formalize it, effectively legitimizing a racial caste system under the banner of “economic necessity.”

Rather than being viewed as full human participants in a transnational labor exchange, these workers were inserted into a political economy built to exploit their mobility while denying them basic rights, permanence, or recognition.

This exploitation of Mexican workers is an economic issue as much as it is a labor one, and it is one deeply tied to the colonial legacy of the U.S. border—a border imposed on their ancestral land.

The continued labor exploitation of minorities today further cements this historic injustice.

The Bracero Program: Exploiting a People on Their Own Land

Even before the first Braceros arrived, the United States had already carved out the legal loopholes through which they would be allowed entry.

As early as 1917, the U.S. made formal immigration exceptions to admit Mexican laborers for agricultural work—only to later criminalize their presence when political conditions shifted.

In Department of Labor records related to the 9th Proviso of Section 3 of the Immigration Act of 1917, the language was clear: the provision allowed farmers to recruit and employ “otherwise inadmissible aliens.”

The terminology betrayed the truth. Braceros were never welcomed as equals, but rather admitted as instruments. Put simply, they were tools of economic necessity—more brown bodies to be exploited by white supremacy.

By the time World War II arrived, that provisional framework had been refined. What began as a wartime exception quietly evolved into official policy.

Launched during World War II, the Bracero Program was framed as a mutually beneficial agreement between the U.S. and Mexico to address labor shortages in agriculture and industry.

However, this narrative conveniently ignored the fact that many of the Mexican laborers recruited under the program were Indigenous to the very lands they were invited to "temporarily" work on.

The lands encompassing the Sonoran Desert, which spans both sides of the man-made border, has been home to the ancestors of Indigenous Mexicans for thousands of years.

For many of these laborers, participation in the Bracero Program was seen as a chance to support their families in a time of economic hardship.

For most, however, the experience fell far short of the contracts' promises of fair pay, sanitary housing, and basic protections.

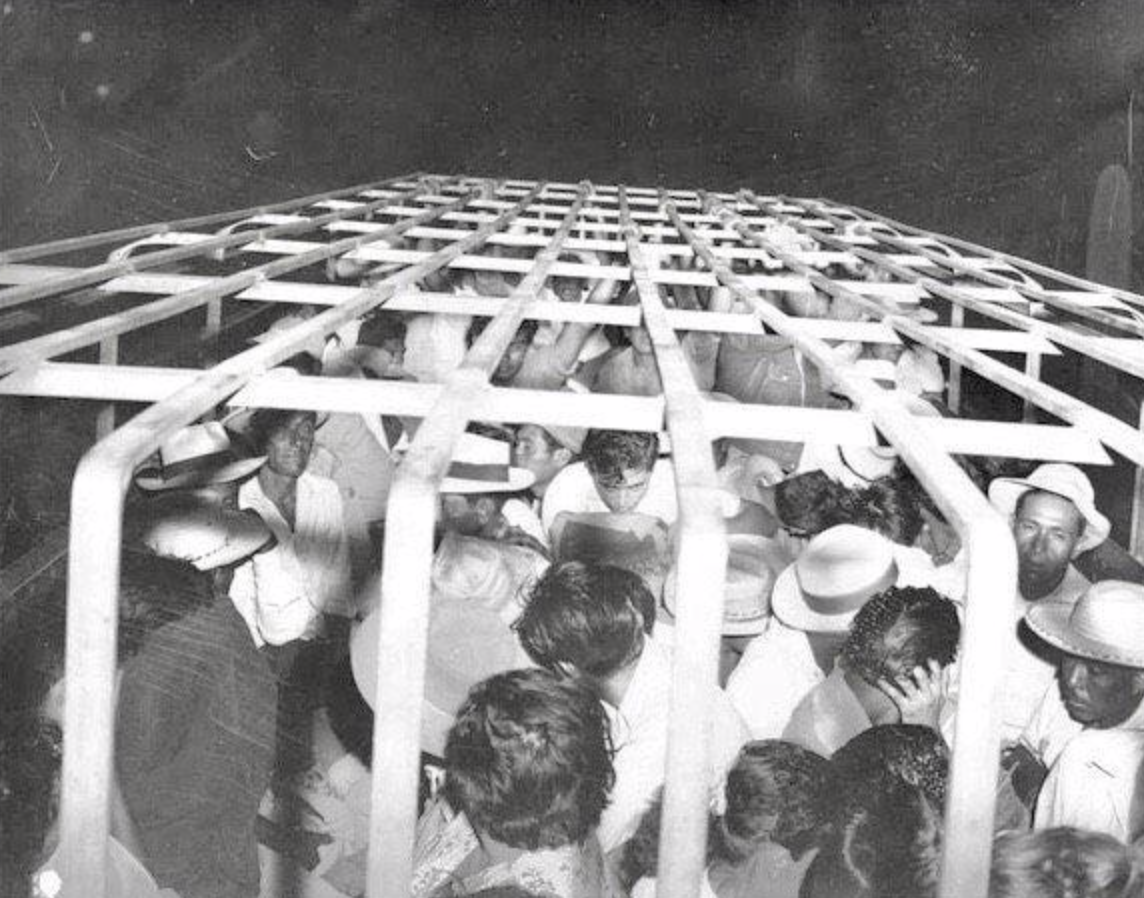

In reality, many Braceros were transported in overcrowded trucks or outdated buses, housed in makeshift encampments without plumbing or sanitation, and exposed to ill‑health and violence on the job.

Workers lived in deplorable conditions, often housed in makeshift shacks with no access to basic amenities.

In places like Phoenix, Arizona, Braceros worked under the searing desert sun, cultivating crops on land that their ancestors had farmed for centuries before European colonizers arrived.

What made the program uniquely cruel was its legal legitimacy—it codified a caste system in which land, once taken through conquest, was made profitable again through the imported labor of those it had been taken from.

The skill and endurance of Braceros were essential to the success of American agribusiness, yet their presence was treated as temporary, and their humanity as secondary to economic output.

Incidentally, the agricultural richness of the region was made possible by Indigenous peoples long before white Europeans arrived and subsequently drew up borders.

Its bounty was maintained by subsequent generations, up until the point of their displacement from the land.

Such a legacy of environmental engineering and ecological balance offers sharp contrast to the collapse of public health and infrastructure unfolding elsewhere in the world during the same era.

While Europe, lacking sanitation infrastructure, was suffering widespread disease during the Black Death, civilizations like the Hohokam were engineering and maintaining expansive canal systems that supported stable agriculture and clean water access in the heart of the Sonoran Desert.

In fact, some of the canals first used by the Hohokam to facilitate and support agriculture are still in use in Arizona to this day.

These Indigenous hydraulic systems were engineering feats—acts of stewardship that challenge the colonial myth that Native peoples failed to develop the land.

Nevertheless, those who managed to remain in the region beyond the establishment of racist border policies of the occupying nation were eventually targeted for “repatriation” into Mexico, even if they were American citizens.

Unsurprisingly, Braceros were treated as disposable, their expertise undervalued, and their connection to the land disregarded.

Racial Supremacy and the Denial of Indigenous Heritage

The deep-rooted racism that Mexican laborers faced during this era was a continuation of the violence and subjugation their ancestors experienced at the hands of European colonizers.

That legacy of conquest endured in new forms—sustained and rebranded through labor policy, border enforcement, and land ownership schemes.

The racial hierarchy in the U.S. relegated Braceros to the bottom of the social ladder, justified by the racist ideology that framed them as inherently inferior.

Classism was also at play, as the agricultural industry was dominated by wealthy white landowners who viewed Mexican labor as nothing more than a commodity to be exploited.

These “landowners,” many of them descendants of settlers who, incentivized by the government, committed genocide in exchange for their land, reaped the benefits of the land’s abundance.

Their wealth was rooted in conquest, and their prosperity was propped up by a racialized labor system designed to extract without accountability.

Such abundance, as is often the case, was made possible by the laborers who worked that land, those who mastered the means of production, yet who were denied fair wages, safe working conditions, and basic human dignity.

What emerged was a caste economy disguised as a free market—where the hands that fed the nation were systematically degraded, devalued, and disappeared from the story of its success.

Operation Wetback: Reinforcing the Theft of Land and Labor

If the Bracero Program represented the exploitation of Mexican labor under the guise of opportunity, Operation Wetback underscored the U.S. government’s view that Mexican workers were a disposable underclass.

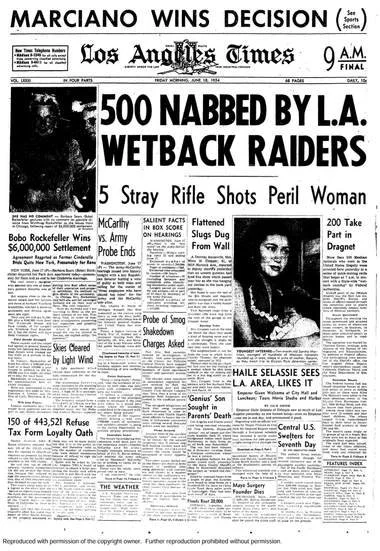

“The so‑called ‘wetback’ problem no longer exists,” INS Commissioner Joseph M. Swing proclaimed in the agency’s 1955 annual report. “The border has been secured” in 1954 under the direction of U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Services with support from local law enforcement and even military resources, Operation Wetback was a federal campaign of mass deportation framed as a crackdown on undocumented immigration—but in practice, it was a racial purge.

Its implementation was marked by widespread racial profiling, indiscriminate raids, and the wrongful deportation of thousands of U.S. citizens of Mexican descent.

People were taken from fields, schools, neighborhoods, and public spaces, often without due process or even time to gather their belongings.

Operation Wetback represented a violent assertion of the U.S. border—an artificial boundary imposed on land that had long been home to indigenous peoples.

Mexican workers, many of whom had crossed this imposed border to work on land their ancestors had farmed, were treated as criminals and forcibly removed from the U.S.

The very term “wetback,” a racial slur, reflected the dehumanizing attitudes toward Mexican immigrants.

It wasn’t just a policy—it was a message: Mexican presence would be tolerated only when it served white economic interests.

Rather than address exploitative labor practices or invest in equitable immigration reform, the state chose to escalate enforcement.

The result was an atmosphere of fear, surveillance, and militarized exclusion that normalized violence against Mexican communities.

The operation not only reinforced the idea that Mexican workers were expendable but also disregarded the historical reality that these workers were the descendants of the first peoples of the land.

Thousands of workers were rounded up and deported, including many who were U.S. citizens.

Their legal status mattered little in the eyes of a system built to preserve white control over labor and land. The operation’s brutality made clear that citizenship was no shield when racialized bodies became politically inconvenient.

These brutal deportation tactics further highlighted the racial supremacy ingrained in U.S. immigration enforcement, where the border was used as a tool to exert white control over land and labor.

The State Declares Itself Victorious

In retrospect, Operation Wetback was regarded by federal authorities as an operational success. It delivered on its promise of mass deportations, made a public spectacle of enforcement, and momentarily silenced political pressure from nativist voices calling for immigration crackdowns.

Joseph M. Swing, the director of the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service, framed the program as a triumph in his 1955 annual report. He reported with bureaucratic finality:

“The so-called ‘wetback’ problem no longer exists. The decline in the number of ‘wetbacks’ found in the United States, even after concentrated and vigorous enforcement efforts were pursued throughout the year, reveals that this is no longer, as in the past, a problem in border control.”

Yet even as he declared victory, Swing issued a warning: the government must not “revert to its operational procedures in effect before the past year.” Prevention, he argued, was now the priority—calling it “more economical and more humane than the expulsion process.”

The order of those terms is telling. Swing framed militarized prevention not as a matter of dignity or justice, but of cost-efficiency. “Humane” became the afterthought, a meaningless boilerplate buzzword that must be included to suggest ethical grounding.

The immigrant remained an “undesirable,” the border remained a tool of racial control, and the state made clear its intent: never again allow migrants enough visibility, presence, or protection to require a repeat of 1954.

Pg. 7 of the 1955 INS report, referring to Mexican as “alien” to the region, despite their indigenous ties to the land.

The Legacy of Exploitation on Indigenous Land

The injustices faced by Mexican workers during the Bracero era and Operation Wetback have left a lasting legacy that continues to shape U.S. immigration and labor policies.

The same racial and class hierarchies that fueled the exploitation of Braceros and the violence of Operation Wetback persist today in the treatment of undocumented workers.

The U.S. economy continues to depend on the labor of migrant workers—especially in agriculture—yet offers them no pathway to security, no guarantee of rights, and no recognition of their historical relationship to the land they sustain.

Today’s immigration enforcement, with its mass raids, family separations, and militarized detention centers, echoes the tactics of Operation Wetback. The targets are the same. The rhetoric is recycled. The trauma is ongoing.

Racial profiling and aggressive deportation campaigns continue to disproportionately affect Latino communities across the country, particularly those living and working in regions their ancestors once called home.

Racial profiling and aggressive deportation tactics continue to disproportionately affect Latino communities, perpetuating the same cycle of violence and exclusion that defined Operation Wetback.

What has changed is not the structure, but the sophistication—surveillance technologies, biometric tracking, and algorithmic decision-making now replace clipboards and flashlights, but the objective remains control.

To speak of immigration reform without reckoning with this history is to perpetuate the very violence it seeks to resolve.

The legacy of land theft and labor exploitation endures—not as memory, but as policy.

Immigration enforcement today, with its emphasis on mass deportations and family separations, echoes the brutal methods used in the mid-20th century.

Reclaiming the Power in Migrant Labor

One cannot reflect on the Bracero era without acknowledging the sacrifices of migrant workers, past and present.

Such recognition is incomplete without a full acknowledgement of the struggles they have faced throughout colonial history.

It is not enough to honor their labor without also confronting the systems that exploited it—systems built on stolen land, racial hierarchy, and legal exclusion.

The Bracero Program and Operation Wetback were not missteps or historical anomalies. They were mechanisms of settler colonialism designed to extract, discard, and erase.

Acknowledging the Indigenous roots of the agricultural practices that sustain the U.S. today is an important step in respecting the past and shaping a more just future.

Yet acknowledgment without accountability becomes performance. Real justice demands more than recognition—it requires restitution, repair, and a radical shift in how we understand land, labor, and belonging.

Mexican laborers, both past and present, deserve to be recognized not only as essential workers but as the rightful stewards of the land—a land that was stolen from their ancestors through violence and colonization.

To reclaim that truth is to challenge the false legitimacy of borders, to resist the narratives that frame migrants as outsiders, and to expose the lies that uphold the mythology of American meritocracy.

Reclaiming the power in migrant labor means refusing to separate labor from land, or workers from history.

It means amplifying the voices of those who have been silenced, and restoring the memory of the first stewards of the earth.

This history is living, it’s ongoing; and with it, so is the struggle to decolonize, to remember, and to rebuild.