Thanks-taking: Your Feelgood Holiday is a Lie

According to the words of the intransigent racist Winston Churchill, “History is written by the victors.” In the case of the fabled first Thanksgiving, that dubious designation belongs to European land usurpers who murdered and maimed their way across this once rich and abundant land.

Thanksgiving. The word itself evokes so many Rockwellian visions of smiling families gathered around a perfectly set table, pausing between bites of turkey and pumpkin pie to express their gratitude for the bounties they’ve been "blessed" with—bounties largely dictated by whatever their capitalist sensibilities have ascribed with value.

The Thanksgiving Myth has long stood as a national fairytale, a fabricated story meant to smooth over the rough edges of brutal settler colonialism.

It paints a picture of a harmonious feast shared by the Pilgrims and the Wampanoag, a tale that conveniently omits the genocide, land theft, and cultural erasure that followed.

Make no mistake, this myth is a historical inaccuracy and a deliberate distortion, designed to make palatable a whitewashed legacy of conquest, oppression and white supremacy.

Sarah Josepha Hale and a White Lie

Just as most events of the settler’s bible were recounted by writers decades after their purported occurrence, the Thanksgiving that you know and love today did not emerge until centuries after the supposed event took place.

Rather than being based in reality, the details of the event were largely shaped by the imagination of Sarah Josepha Hale, a 19th-century writer and noted opponent of women’s suffrage.

Such an inclination toward revisionism further mimics the Puritan’s holy text, in the sense that it, too, has been bastardized by translations, retranslations, removing or adding of passages (and entire books altogether) to fit the political or ideological agendas of kings, popes and other ruling powers.

Often referred to as the “Mother of Thanksgiving,” Hale was the prolific writer and editor of Godey’s Lady’s Book, one of the most influential publications of the 19th century.

Hale had a vision for Thanksgiving—not as a regional or familial celebration but as a national tradition that could serve as a moral and cultural anchor, as it were, for the United States.

Amidst the massive bloodletting of the Civil War, Hale championed the holiday as a unifying tradition, crafting an idyllic story of harmony that ignored the brutal realities of settler colonialism.

Beginning in the 1820s, Hale used her platform to advocate for the holiday, writing editorials, essays, and letters to prominent politicians, including five U.S. presidents.

She framed Thanksgiving as an opportunity to celebrate family, morality, and unity—a narrative that conveniently ignored the violent foundations of the Pilgrims' survival and the subsequent colonization of Native lands.

By transforming a fleeting moment of mere spatial coexistence into a symbol of national identity, Hale’s romanticized Thanksgiving myth became a tool with which to whitewash genocide and dispossession.

The 1621 Harvest Festival: The Seed of a Myth

The so-called "First Thanksgiving" was, in reality, little more than a diplomatic effort. Hardly the fabled seasonal jamboree based on mutual admiration, the event was a three-day harvest feast designed to normalize tenuous relations between the Wampanoag and European settlers.

Interestingly, the 1621 feast shared by the Pilgrims and the Wampanoag was never referred to as “Thanksgiving” by the colonists; it was merely a commemoration of a successful harvest, due, in large part, to the sharing of agricultural knowledge by the Natives, who by that point, had been cultivating the land for upwards of 10,000 years.

The term “Thanksgiving” was used later, in July 1623, for a solemn day of prayer and fasting. This religious observance was entirely unrelated to the fall harvest and bore little resemblance to the modern holiday.

While both the Wampanoag and Pilgrims are reported to have participated in the 1621 event, there is no indication that it was a unified act of gratitude or a foundational moment of shared values.

The attendance, for instance, of Massasoit Sachem, the leader of the Wampanoag confederation, served to reinforce the tenuous peace treaty that existed between the two groups, ensuring his people's survival in an increasingly hostile environment.

Massasoit sought to ensure the tribe's survival through an alliance that provided mutual benefits: the Wampanoag offered agricultural and geographical knowledge necessary for survival, and the Pilgrims provided potential military support against any rival factions.

“Mystic Massacre in New England” (1638). A description text reads: “Facsimile made by Edward Bierstadt, from the original in the library of the New York Historical Society, of the Map in ‘Newes from America,’ an account of the Pequot War, by Captain John Underhill, published in London in 1638. The Fort was referred to as ‘Seabrooke Fort’ and ‘Lyes upon a River called Conetticut [SIC] at the mouth of it,’ and ‘the destroying’ occurred May 19, 1637.” (via Wikimedia Commons)

The Collapse of Peace: From Gratitude to Violence

The tension between colonists and Indigenous tribes reached a breaking point in 1637, by way of the Pequot War. While the conflict involved multiple players—Pequot, Narragansett, Mohegan, and English settlers—it was ultimately the Pequot tribe that bore the brunt of colonial aggression.

The settlers accused the Pequot of attacking English settlers, though these claims were often exaggerated or falsified to justify violent retribution against Natives.

In May of that year, English settlers, aided by Narragansett and Mohegan allies, launched a pre-dawn attack on the Pequot village of Mystic. The colonists set fire to the village, burning alive hundreds of Pequot men, women, and children inside.

Those who attempted to confront the mercenaries were either shot, clubbed to death, or otherwise captured as slaves.

These Puritan soldiers then continued onward in their rampage, visiting village after village, brutally marauding and pillaging, capturing surviving women and children over 14 as slaves, and murdering the rest.

By comparison, those who had perpetrated the attacks were rewarded handsomely with vast acreage of land.

Another Colonial Thanksgiving

Following the bloody campaign of death, Governor John Winthrop of the Massachusetts Bay Colony declared a day of thanksgiving to celebrate the settlers' violent triumph.

This proclamation came after English settlers, with the aid of rival tribes as allies, had effectively ethnically cleansed the region of its Indigenous inhabitants.

The irony of celebrating mass violence under the guise of divine providence, while simultaneously laying the framework for a vision of moral superiority, exemplifies the glaring contradictions of colonial narratives, many of which still pervade the American narrative.

Winthrop, a slave owner who fancied himself a paragon of "Christian charity," is further notable in history as the originator of the famous phrase "City on a Hill."

First articulated in a 1630 sermon by Winthrop, this term has since been invoked by numerous political figures, including John F. Kennedy, Ronald Reagan, Barack Obama, Mitt Romney, James Comey, and Mike Pompeo, underscoring the enduring concept of American exceptionalism.

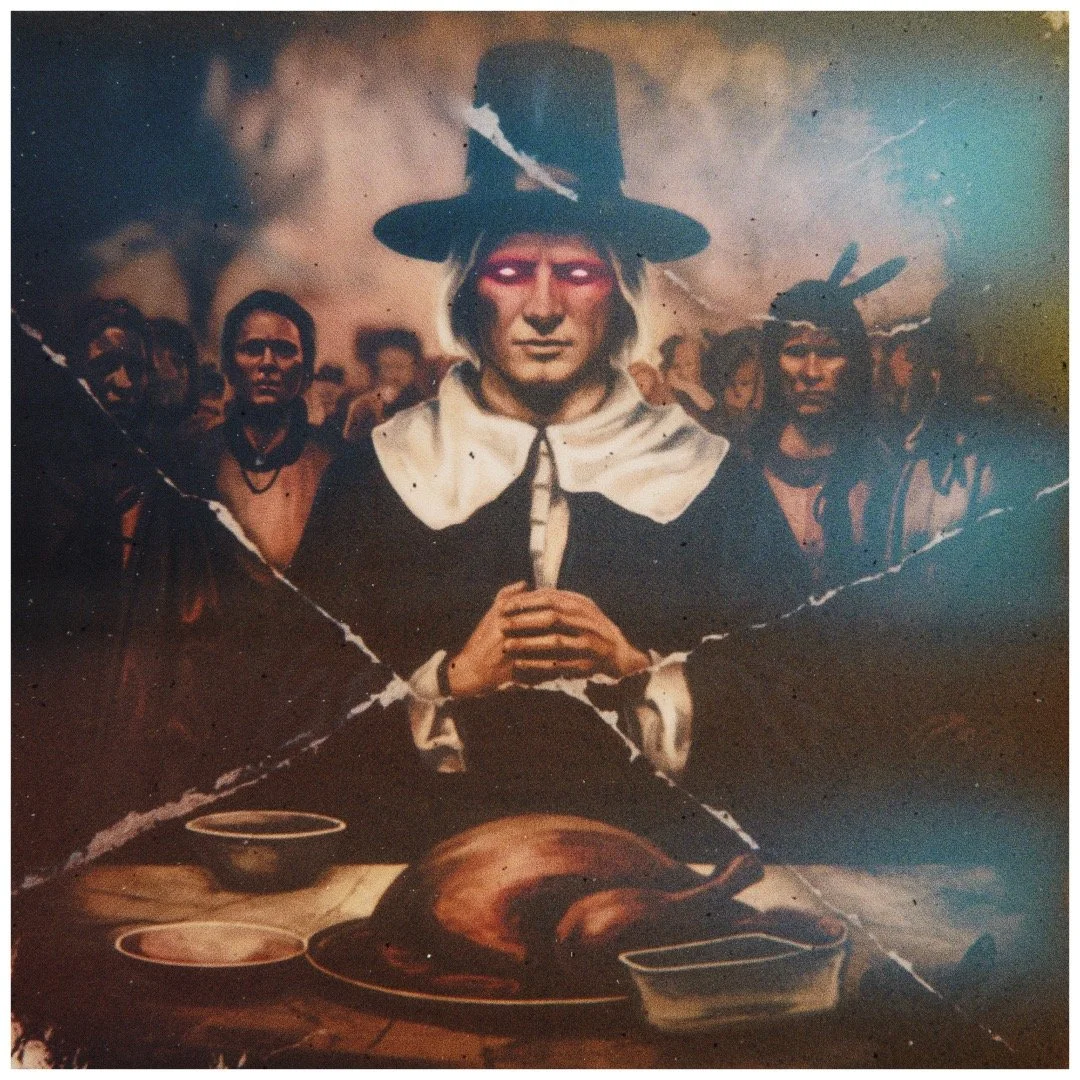

Behold, the face of John Winthrop, a man of purportedly “superior” White genetics

By framing the massacre as an act worthy of giving thanks, the colonists justified their actions through a lens of divine approval, and their victory as providence.

The proliferation of this narrative served multiple purposes: it reinforced the settlers’ belief in their God-given right to the land, validated their violence as a necessary act of survival, and cast Indigenous resistance as a threat to be eradicated.

To put it mildly, this early instance of a "thanksgiving" set a morbid precedent. By linking violent conquest with religious celebration, colonial leaders established a tradition of masking atrocities under the guise of pious humility and quiet gratitude.

Such declarations quickly became a recurring practice, with subsequent massacres of Indigenous tribes often marked by similar “thanksgiving” observances.

King Philip’s War: The Violent Legacy of Thanksgiving

What Massasoit’s diplomacy had staved off, it could not prevent completely, and thus the breakdown of relations between the Wampanoag and the Pilgrims was inevitable. By the time of his death in 1661, the fragile peace he had worked so hard to maintain was already unraveling.

His son, Metacom—known to the settlers as King Philip—would inherit not only his father’s leadership but also the full weight of betrayal and displacement wrought by the settlers.

By the 1670s, the settlers’ insatiable desire for land had reached a boiling point. Despite the initial treaty, the Pilgrims and their descendants began systematically encroaching on Wampanoag territory, stripping the tribe of their land, resources, and sovereignty.

Metacom, recognizing the futility of attempting to reason with these White supremacist land usurpers, began organizing a confederation of tribes to resist colonial domination.

The resulting conflict, King Philip’s War (1675–1678), was one of the bloodiest in American history. Thousands of Native people were killed, and survivors were sold into slavery or forcibly displaced.

This war effectively ended Indigenous resistance in southern New England, paving the way for unchecked colonial expansion by an influx of White European settlers.

Once again, the settlers’ victory was celebrated as a divine endorsement of their bloody conquest through the giving of thanks, further solidifying the Thanksgiving myth as a narrative of omission and repression rather than peace and harmony.

At one point, the frequency of these post-massacre “thanksgiving” celebrations became so much that George Washington himself suggested that the settlers set aside one day a year to give thanks for their success in slaughter.

Thanksgiving as a National Holiday: A Story Rewritten

Thanksgiving officially became a national holiday in 1863, during the height of the Civil War. Abraham Lincoln’s proclamation sought to unite a fractured nation by rebranding the holiday as a celebration of perseverance and gratitude.

Fortunately for the famed Indian murderer Lincoln, Sarah Hale’s narrative had come along decades prior, and was ripe for the picking.

This reinvention sanitized the violent origins of the tradition, embedding a false narrative of harmony and progress into the national consciousness.

For many Indigenous peoples, however, Thanksgiving is a different day, indeed. Observed as the National Day of Mourning, it honors the ancestors who suffered under colonization and resists the ongoing erasure of Indigenous histories.

By reframing the holiday as a time for reflection, Native communities challenge the dominant narrative and assert their resilience and a resistance to the prevailing, markedly false narrative.

Decolonizing the Thanksgiving Narrative

Confronting the Thanksgiving myth is not about erasing tradition but about reframing it with honesty and integrity.

The contributions of the Wampanoag—the unwitting wards charged with the survival of helpless, bumbling Pilgrims—have been overshadowed by a narrative that glorifies colonizers while erasing the atrocities they committed.

Perhaps that is the one truly American value, the last thing actually manufactured in this unearned country filled with so many jackals:

A penchant for laundering the past by replacing real events with more palatable tales that align with the sensibilities of a populace decidedly more interested in self-righteousness than self-awareness.

Where once, there was death and displacement, there is now a completely fabricated friendship between two seemingly equal and benevolent groups of people.

Like all fairytales made in the USA, this myth, incongruent as it may seem with the actual arch of history, is the only truth that matters to a group too preoccupied with its own arrogant hubris to perceive of, let alone anticipate for, its own looming, inescapable collapse.

Rejecting the Myth

Put simply, the Thanksgiving myth is a tool of colonial erasure that sanitizes the barbaric realities of conquest.

The whitewashed account of Sarah Hale, combined with the colonial Thanksgiving declared after the Mystic Massacre, reveals the moral hypocrisy at the heart of the settler narrative.

Cloaked in the self-indulgent frills of gratitude and the lavishness that only the deepest ignorance can provide, the destruction of a people and the expansion of colonial control lies at the heart of the Thanksgiving celebration.

The massacre, and the rewards that followed, underscored the settlers’ view of the land as a prize to be won and Indigenous lives as disposable. This has been underscored time and again in the intervening centuries, by a nation hellbent on making sure the true Indigenous of this land remain the minority.

Upon waking up to the truth about Thanksgiving, one might experience a number of emotions—anger, heartbreak, sadness, etc.

It’s understandable. There is nothing particularly desirable about learning you were willfully misled by the United States institution, for the purpose of the continuation of an ill-gotten nation and its people.

Above all, it should spark a righteous indignation and inspire an unwavering commitment to truth, equity, and the voices of those who have endured centuries of systemic harm. Reckoning with this past is the first step in building a more inclusive and equitable future on a land that, for better or worse, is being shared by conqueror and native alike.