Forgotten Atrocities: Reflecting on Hiroshima and Nagasaki

The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were not acts of wartime necessity, but calculated war crimes.

Like most people who, through no accomplishment of their own, happened to spawn to life in the US, my understanding of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki was long shrouded by the grimy lens of American™ history.

I never questioned it. The justification for quite literally incinerating hundreds of thousands of innocent civilians was some foregone conclusion that had been determined long before I got here.

Therefore, my complicity in a system that accepts such a conclusion could easily be excused by ignorance, at least by an ostensibly “polite” society that operates within and subsists upon a world of “alternative facts.”

The truth? There is no justification for the level of carnage unleashed upon not one, but two, civilian populations—not even the sacrosanct Pearl Harbor attack that this nation likes to use as an inexhaustible victim card.

To be clear, the attack on Pearl Harbor did not occur in a vacuum, but rather was a direct response to the economic and political pressures that Japan faced due to American-led sanctions and embargoes.

For generations, the narrative has been clouded by the American perspective—a viewpoint that seeks to justify, or at the very least, rationalize the unspeakable horrors unleashed on Japan 79 years ago today.

Ask someone who was born outside of the grasp of Imperialist chronicling of history.

Chances are, they’ll view these events quite differently, in ways that demand examination and an accountability for the bombings, which, as it turns out, were less about wartime necessity, and more about a cold-blooded, vulgar display of power.

Racist 1941 US propaganda poster featuring Uncle Sam threatening genocide, saying “JAP… You’re Next!” and “We’ll Finish the Job!”

Pearl Harbor: Propaganda That Justified Genocide

The bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, is frequently cited as the catalyst that propelled the United States into World War II, and subsequently, as the moral justification for the dropping of two nuclear bombs on populated cities.

However, despite the official declaration of its entry into World War II on December 11—four days after the bombing at Pearl Harbor—the United States had already been deeply involved in the conflict.

In 1940, the U.S. imposed an embargo on iron and steel exports to Japan, and by mid-1941. The situation intensified when the U.S. froze Japanese assets and imposed an oil embargo.

This action was a severe blow, as Japan imported over 80 percent of its oil from the United States.

Objectively, these blockades were clear acts of Western aggression—specifically, American provocation—designed to cripple Japan’s economy.

The U.S., under the Lend-Lease Act, was acting at the behest of its European allies already deeply entrenched in the world war.

Put simply, the United States was already a proxy participant well before its official entry into the global conflict.

Of course, one thing that is hard, if not impossible, for jingo-blind Americans to understand is the nature of its nation’s deeds in their proper context.

Pearl Harbor was, in every sense, a military strike. It targeted a naval base that housed the very forces posing a direct threat to Japan.

According to the laws of war, this was a legitimate military target.

The attack, though devastating, was not an indiscriminate assault on civilians; it was a calculated, strategic move in the so-called theater of war—a preemptive strike aimed at impeding the U.S. Pacific Fleet.

In stark contrast, the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were not directed at military installations but at civilian populations.

Incendiary Prelude to Nuclear Annihilation

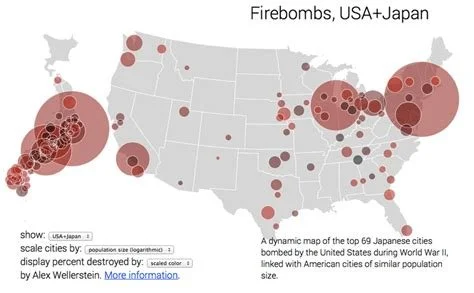

Well before the the Fat Man and Little Boy were loaded onto bombers, Japan had already been reeling from a long-sustained conventional bombing campaign.

Between 1943 and 1945, Japan sustained near-constant conventional-bomb air raids.

The most infamous of these, the Tokyo air raid, saw over 300 bombers drop nearly 1,700 tons of explosives, killing an estimated 100,000 civilians in a single night.

It was the deadliest conventional air attack in human history. Entire neighborhoods were erased, leaving more than one million people homeless.

Other cities—Osaka, Kobe, Yokohama, and Nagoya among them—suffered similar fates.

In total, the campaign of incessant raids and forced displacement policies had uprooted approximately 10 million Japanese civilians, scattering populations across the country and compounding the human toll of the war.

By the summer of 1945, many urban centers were reduced to charred ruins, their survivors facing starvation, homelessness, and disease.

Seventy-Two Hours to Oblivion

The nuclear bombings by the United States stand alone in the annals of warfare as the only instances where nuclear weapons have been used against human beings.

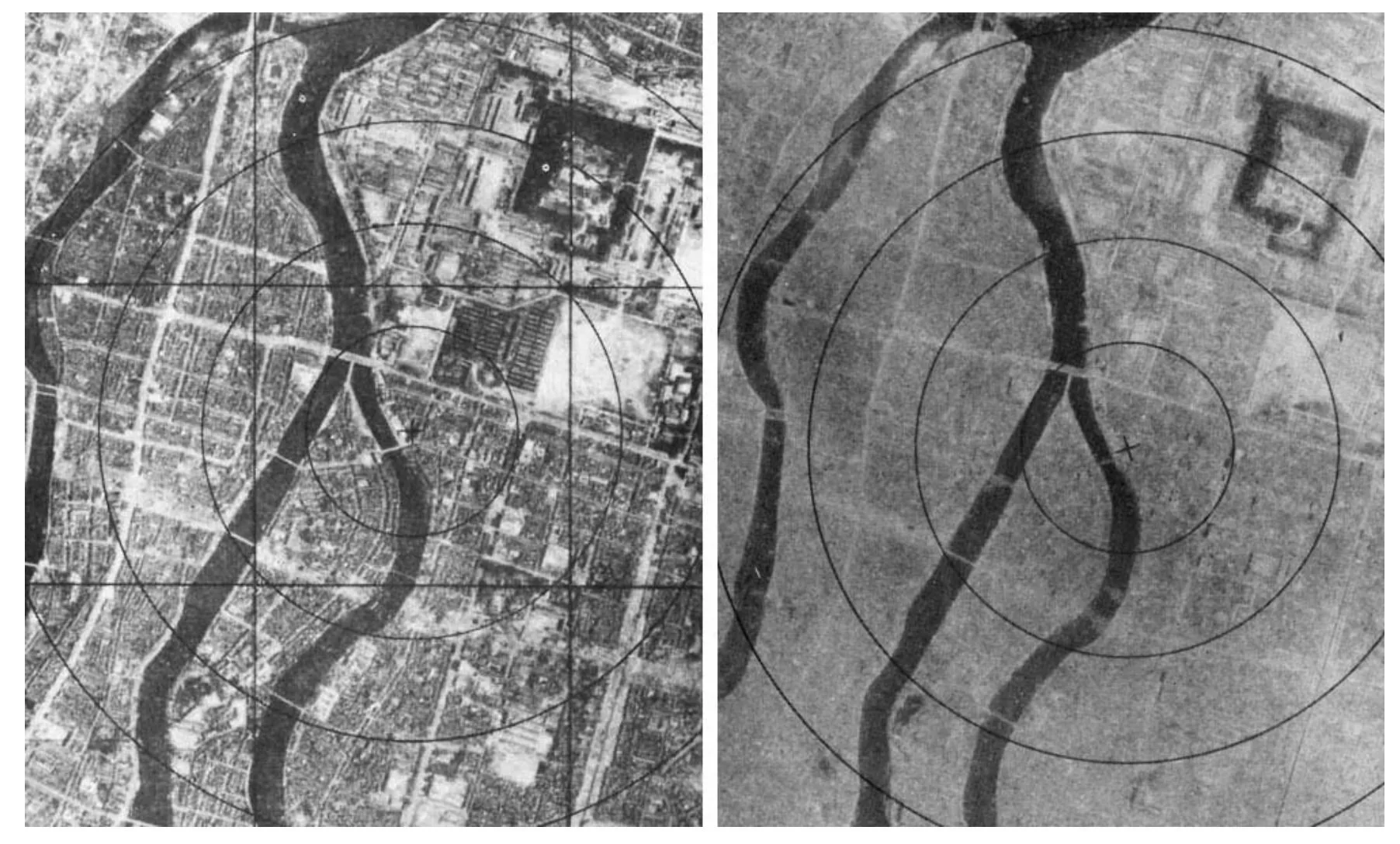

On August 6, 1945, at 8:15 a.m. Hiroshima time, the B-29 bomber Enola Gay dropped the uranium-235 bomb “Little Boy” over the city.

The weapon detonated roughly 1,800 feet above the ground, unleashing a force equivalent to 15 kilotons of TNT, instantly vaporizing entire neighborhoods and flattening about 5 square miles—destroying over half the city's structures and killing tens of thousands immediately.

Just three days later, on August 9, 1945, at around 11:02 a.m., the B-29 Bockscar dropped a plutonium-239 bomb, “Fat Man,” on Nagasaki.

Estimated to generate a yield of 21 kilotons, it detonated over the city’s industrial Urakami district, killing an estimated 27,000 people instantly and ultimately bringing Nagasaki’s death toll to around 70,000 by the end of 1945.

These staggered attacks—a meticulously timed apocalyptic display—were meant not only to expedite the end of the war but to deliver profound psychological shock.

In less than 72 hours, two cities ceased to exist, reshaping global history through the terrifying realization of nuclear destruction.

340,000 Lives Lost

In Hiroshima, approximately 140,000 people were killed by the nuclear attacks by the end of 1945, while Nagasaki saw about 74,000 fatalities in that same timeframe.

The majority of these victims were civilians—men, women, and children—who had no role in the war, just the misfortune of living in a country that was at odds with the United States.

By 1950, total death estimates reached around 200,000 in Hiroshima and 140,000 in Nagasaki.

The aftereffects of the atomic bombings continued to claim the lives of Hibakusha, those who survived, for years to come.

Radiation sickness, cancers, and other long-term health complications continued to claim tens of thousands more lives in the ensuing years.

The deliberate targeting of civilians in such magnitude fits the modern legal definitions of war crimes. There is precedent.

The Nuremberg and Tokyo Trials prosecuted individuals for comparable atrocities—yet the American architects of these bombings never faced accountability.

The majority of these were civilians—men, women, and children who had no role in the war other than the misfortune of living in a country that was at odds with the United States.

The Hubris of Power: Why America Chose Mass Murder Anyway

The decision to drop atomic bombs on Japan was not born out of military necessity, as has often been claimed.

By the summer of 1945, Japan was on the brink of surrender. The Japanese government, fully aware of its dire situation, had already initiated negotiations with the Soviet Union, seeking to broker peace.

The only sticking point in these negotiations was the status of Emperor Hirohito.

Japan was willing to surrender on the condition that the emperor, a figure of immense cultural and spiritual significance, would be allowed to retain his position, in order to ease the transition into a post-war era.

However, the United States, driven by a combination of racial animus, a desire for revenge, and an itchy trigger finger wishing to demonstrate its newfound nuclear might, refused to entertain any conditional surrender.

American leaders, particularly President Harry S. Truman and his advisors, were determined to impose an unconditional surrender, one that would strip Japan of its imperial system.

The bombing of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, followed by the bombing of Nagasaki on August 9, 1945, was intended to compel Japan to accept these terms.

Yet, in a cruel twist of irony, the very condition that Japan had sought to preserve—the retention of the emperor—was ultimately granted, even after the bombings that completely devastated a nation.

Hirohito remained on the throne; a symbolic gesture that highlights the needless destruction wrought by the atomic bombs.

Japan's surrender on August 15, 1945, was not the result of the bombings alone, but of a combination of factors, including the bloody atrocities at Iwo Jima and Okinawa.

The bombings, therefore, were a physical manifestation of American hubris itself—an insistence on demonstrating the overwhelming power of the United States, regardless of the human cost.

The aftermath of the atomic bombing of Nagasaki via Wikimedia Commons: Koyo Ishikawa

American Concentration Camps: Components of Domestic Racism and Collective Punishment

The United States’ self-image as a moral authority in World War II—and as arbiter of who may possess nuclear weapons—is undermined by its treatment of Japanese American citizens during that same era.

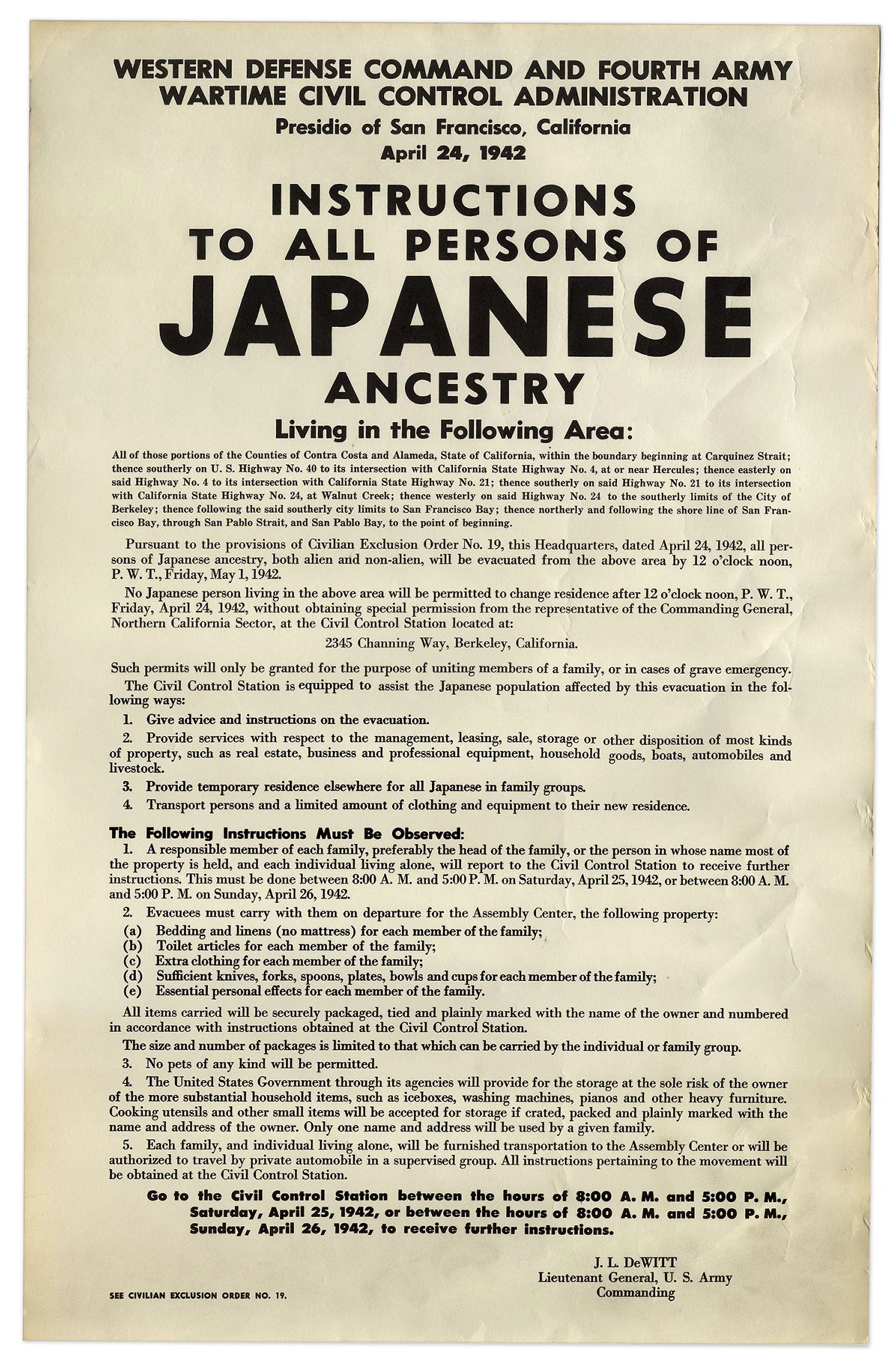

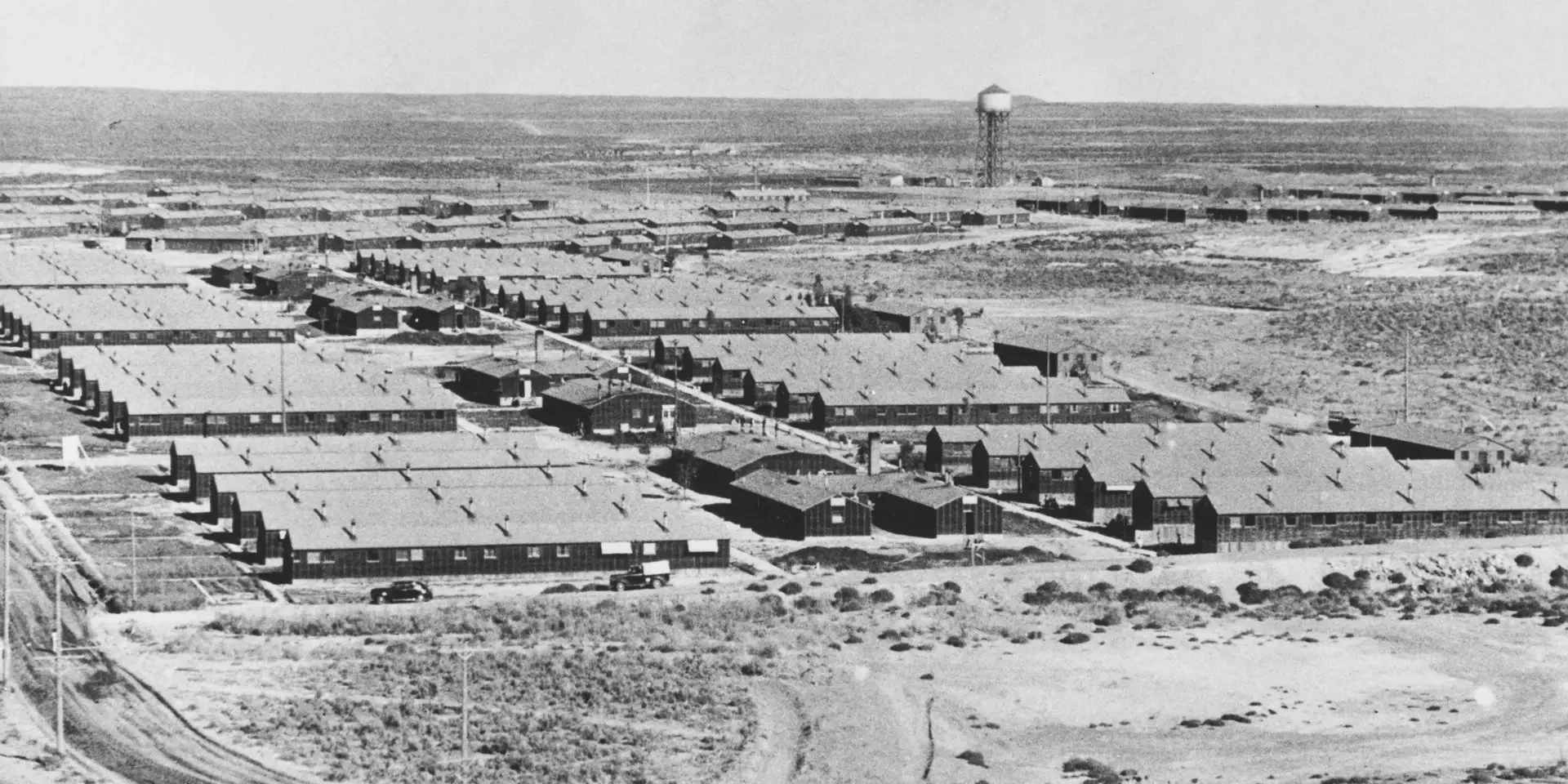

In the wake of Pearl Harbor, the U.S. government forcibly relocated and incarcerated over 120,000 Japanese Americans in internment camps, a euphemism for what were effectively concentration camps.

These camps, located in remote areas of the country, were overcrowded, unsanitary, and guarded by armed soldiers.

Families were torn apart, and individuals were stripped of their property, livelihoods, and basic human dignity—all based on their ethnicity, not any proven disloyalty.

The parallels between these camps and the concentration camps of Nazi Germany are uncomfortable, but undeniable.

While the American camps did not engage in the systematic extermination of their inhabitants, they were nonetheless a grave violation of civil rights and human decency, for adults and children alike.

The internment of Japanese Americans was driven by the same racist ideology that justified the use of atomic bombs on Japanese civilians—the same that Germany used to justify the internment of Jewish prisoners into its concentration camps.

A Reckoning Long Deferred: America Still Refuses to Acknowledge Its War Crimes

The narrative of World War II, as told from the American perspective, is woefully incomplete without reckoning with the atrocities committed by the United States itself—atrocities that have been obscured by the false glow of ill-gotten victory.

The bombings of two Japanese cities weren’t acts of valor, but of unparalleled cruelty. Furthermore, the internment of Japanese Americans was not a protective measure, but a gross violation of human rights, born of fear and prejudice.

As the only nation to have ever used nuclear weapons in war, the United States bears a unique responsibility to confront the legacy of these bombings.

Its citizenry must acknowledge the suffering inflicted upon the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, not as collateral damage in a just war, but as victims of what, until that point, was an utterly unfathomable crime against humanity.

Japanese-American Internment Camps in the United States

In the shadow of these nuclear attacks—which to this day remain the only such aggressions unleashed on civilian populations—the world has been forever changed.

The atomic age, ushered in with such horrific violence, serves as a reminder of the devastating power that humanity now possesses.

With such immense power comes a collective moral imperative—to ensure that such weapons are never used again, and to remember the lives lost in the name of empire.

That obligation extends far beyond symbolic gestures; it demands substantive policies, unwavering commitment to human rights, and unflinching honesty about the past.

Yet the same ethos of American and Western exceptionalism that justified Hiroshima and Nagasaki continues to shape today’s theaters of war.

From drone strikes on wedding parties to proxy wars that devastate entire regions, the tools and technologies have evolved, but the arrogance remains intact—still cloaked in the language of liberation, still excused by the fiction of moral necessity.

Only by acknowledging and fully accounting for these atrocities—past and present—can we ensure that a nuclear attack like that of the United States against Japan never happens again .